Ultrasound - the future of Parkinson's care?

Only if the NHS will pay

Last week I was invited to a hospital to see some brain surgery taking place. But this operation did not involve a single scalpel and the team of surgeons and neurologists involved were in their normal clothes rather than scrubs. In fact, for most of a procedure lasting two and a half hours the doctors were looking at their patient from behind a screen in a setting which looked more like Mission Control for a space mission than an operating theatre.

What I was seeing at London’s Queen Square Imaging Centre was something called focused ultrasound and my host was Professor Ludvic Zrinzo, a pioneering specialist in using Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) to treat Parkinson’s. Professor Zrinzo, who operated on my Movers and Shakers colleague Gillian Lacey-Solymar, is extremely excited about the potential of this new technique.

“I don't say this lightly, DBS was the biggest surgical innovation for Parkinson's, and I think this is the next big thing.”

Video of focused ultrasound patient Ian King before and after the operation

We think of ultrasound as something used for scans of babies in the womb or other views of what is going on inside the body but here it is used at high intensity literally to burn away unruly brain cells. The ultrasound device is paired with an MRI scanner enabling the doctor to focus the beam of energy with great precision. Its proponents believe the technique has a wide variety of applications, including treating mental health conditions such as OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder) as well as neurological ailments.

At Queen Square, one of just three locations in England to have invested in the expensive equipment needed for focused ultrasound, they are at first mainly using it to treat essential tremor. This condition, often confused with Parkinson’s, involves just the one symptom of that disease but can be extremely debilitating - the NHS says 250,000 people in Britain are severely disabled by it.

The first of two patients treated on the day I visited, a man in his mid-60s - let’s call him ‘Andy’ - told me he had had essential tremor for thirty years. It had caused him acute embarrassment, both in social situations and in his work in the telecoms industry. He remembered an occasion when a colleague had to take over in the middle of a presentation he was giving because he could not move the mouse.

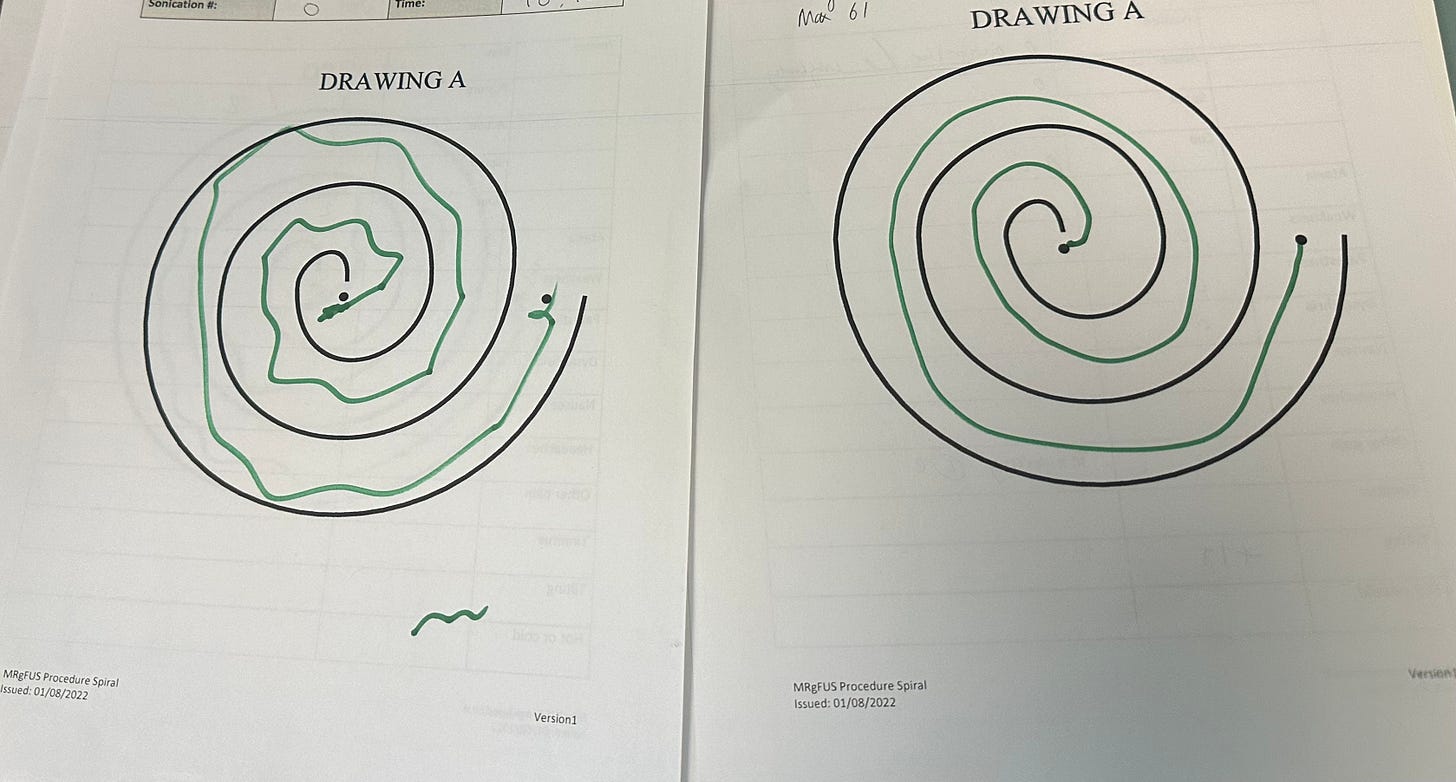

‘Andy’ arrived with his head closely shaved - hair can trap air bubbles that can cause a nasty burn on the scalp as the intense energy passes through the skull. Next, a frame was attached to his head to keep it still and enable precise targeting of the ultrasound. Then a series of tests to assess the state of his tremor before the operation. He was asked to draw a spiral as closely as possible to one printed on a sheet of paper, then to lift a cup of water to his lips. His spiral was all over the place, and he laughed as the water from the shaking cup went everywhere but his mouth.

Finally, ‘Andy’ was loaded into the MRI scanner and Professor Zrinzo and the other doctors retired to “mission control”. A clutch of the National Hospital’s top neurologists was there to participate or just to observe - a marker of the hospital’s aspirations to expand its focused ultrasound programme. As we will find out later, that depends on getting the NHS to pay for it.

Also in the control room was an expert from the company which supplies the ultrasound technology. He sat alongside the doctor who would be “firing” the ultrasound beam from a computer. I had been told that the moment when the targeted brain cells were destroyed might only last a maximum of twenty seconds but first there was a lot of painstaking preparatory work.

The screens in the control room showed a live feed of ‘Andy’ in the MRI scanner and a cross-section of his brain with the target area mapped out. After making sure the patient was correctly positioned in the scanner the ultrasound surgeon did a number of test firings at a low intensity to make sure the target was being hit without the possibility of collateral damage to other parts of the brain.

Each time, there were intense discussions between Professor Zrinzo, his medical colleagues and the technician from the focused ultrasound supplier, about the duration and intensity of the beam. After each firing, Andy was brought out of the scanner to check he was ok and to give him another round of the tests assessing his tremor.

Finally, after two and a half hours, Professor Zrinzo gives the go ahead for a beam that will last twenty seconds and “cook’ the targeted brain cells to a temperature above 60°C. The patient is finally released from the scanner - anyone who’s had an MRI can imagine how gruelling a two and a half hour spell in one can be - and has the frame around his head removed. And the results of his tremor test are dramatic - he produces a near perfect spiral and lifts the plastic cup of water to his lips and drinks without spilling a drop.

‘Andy’, although somewhat exhausted by his morning in the scanner, leaves very satisfied by the result and it seems clear that focused ultrasound can be a very effective treatment for essential tremor. But selfishly I want to know what the procedure can do for Parkinson’s, and in the waiting-room I find the next patient, who may be able to tell me.

70 year old Ian King is a retired painter and decorator and says he is happy for me to tell his story. I notice that he has quite a severe tremor in his right arm and leg. Professor Zrinzo has told me that at the moment guided ultrasound is most suitable for people whose main Parkinson’s symptom is a one-sided tremor. But he says encouraging research suggests that a modified form of the procedure might help other symptoms, like slowness and stiffness, as well.

Ian, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s six years ago, says he has been told that the operation has an 80% success rate and he’s hoping that he will be able to get back into golf. He asks me whether I am interested in having focused ultrasound and I tell him that I am wondering whether it might be a good alternative to DBS - which, it turns out, neither of us fancies. But, as I leave, he seems understandably a little nervous about this operation - even if it takes around half the time of a DBS procedure, the idea of having irreversible changes made to the way your brain works is daunting.

I am unable to stay for Mr King’s operation but he gives me his phone number and a couple of days later I give him a call to find out how it went. “Very very well” he told me. “I haven't any tremor in my right leg or right hand, not a bit. I keep holding my right arm out and thinking ‘don’t shake’ and it doesn’t!” When, with Mr King’s permission, Professor Zrinzo sends me the ‘before’ and ‘after’ videos of the tremor tests that you can see at the top of this post, it is clear that the ultrasound treatment has been very effective.

Ian King said his operation had been quite unpleasant and when they had extracted him from the scanner for the seventh time for some tests he had been ready to say that was enough - but they told him he was done. Then he did the cup of water test, raised the plastic beaker to his lips and said ‘Cheers’ to the medical team. There are some side effects - he feels a bit unsteady on his feet and has been told that will last a few weeks, but after that he is looking forward to getting back on the golf course.

Surely, given these impressive results, plenty of people with Parkinson’s will be asking their neurologists about focused ultrasound? If they do, they will be told there is a waiting list of at least five years for the operation - unless they want to pay to go private. That is because the NHS only provides limited funding for this novel treatment, and none of that is available to the National Hospital - ‘Andy’ and Ian King have paid a hefty sum for their operations, though both say it is well worth it.

Ludvic Zrinzo is immensely frustrated by this situation, particularly as the equipment needed for the procedure has been funded by the charitable foundation which supports the hospital meaning that the NHS would not need to provide any capital investment. He sees focused ultrasound becoming one of a range of tools doctors can offer people with Parkinson’s, along with DBS, medication, and the duodopa pump.

He is impatient for a positive decision that will allow NHS patients to be treated by the Queen Square machine. “We really want to give NHS patients access to the whole surgical toolbox. If all you have is a hammer, then that's the end of it, that’s the only tool you're going to be able to use.”

We all know about the financial pressures the NHS faces and I am sure every specialist has some new treatment they think should be funded. But thank goodness that Parkinson’s, way down the pecking order in terms of investment in key staff and research, has someone as passionate as Professor Zrinzo prepared to make a noise about the neglect of so many people.

FUS has been available in Switzerland for some years. The doctor who has performed many FUS PTT treatments on PD sufferers, Dr Jeanmonod, has recently retired, so his partner Dr Marc Gallay is setting up a new clinic in Berne. The previous one was in Sonimodul . It is also available in Spain.

There is a FB group where quite a few people have had the treatment, and mostly positive results. The USA has ran a project in many states within the last 2 years giving this treatment under research conditions. It isn’t a cure but comes very close to a solution to live life without too many symptoms.

My husband who has PD has been following results of this treatment. On Health Unlocked under Cure Parkinson’s Trust are many patients round the world who have had this treatment.

The treatment is mainly effective, some patients have had side effects, it is down to zapping the correct part in the brain, by a skilled operative, and that’s putting it lightly!

How exciting! Perhaps a fundraising effort with high profile donors would bring attention to this marvellous new treatment!