Dr Google or Professor Twitter?

Seeking medical advice online

Where do you go for medical advice about a condition that is annoying, could be harmful in the long-term, but poses no urgent threat to life or limb? At a time when getting a GP appointment can seem as hard as getting tickets for the Wimbledon finals. it is an issue on the minds of many.

For me, it was a sudden drastic worsening of my insomnia which got me thinking. In the third week of my online cognitive behavioural therapy course, just when I seemed to be making a bit of progress, I had two disastrous nights. On both occasions, I simply could not fall asleep. I tried everything - listening to a dull podcast (too interesting again), remembering every Brentford Premier League result this season, going back through childhood memories.

The latest session of my CBTI course had explained a technique called Progressive Relaxation. In a ten minute audio file which I had downloaded the “Prof”, with his gentle soothing Scottish voice, instructs you how to tense and then relax various muscles while slowly breathing in and then exhaling while saying “relax’.

The trouble was that I had a constant case of the fidgets, unable to get comfortable in any position, which meant that halfway through the lesson I had to stop because it became too painful. The first night, I slept no more than half an hour or so, on the second I was still awake at 4 a.m. so got up and tried without success to fall asleep on the sofa. After 48 hours with barely any sleep, I found it hard to function, nodding off during an important video call on Friday.

So what to do? Most of us in these circumstances turn to Dr Google for advice. Some GPs relate with great exasperation how patients turn up at consultations with sheaves of paper printed out from internet searches about their supposed ailments, and look back wistfully to the days before the internet when the doctor was the fount of all wisdom.

My sympathies are divided - surely it is a good thing that the internet has enabled us to become better informed as patients, but my own experience tells me that a quick Google search can also cause great harm to your morale.

Late in 2004 I was diagnosed with a malignant melanoma behind my left eye. Doctors at Moorfields Hospital told me that I would need to have an operation to place a radioactive plaque behind my eye to shrink the tumour, A couple of months on I was booked in for the treatment which would involve spending a week in a lead-lined room at Moorfields.

But beforehand I decided to Google my condition. The first result was a link to a medical paper which described a patient who had presented at hospital with symptoms similar to mine. Six months later, he was dead. Terrified, I quickly closed down the computer and for years afterwards did not enter the term ‘ocular melanoma’ into a search box again. Instead, I relied on the wisdom of my Moorfields doctors who turned out to be not just good at their jobs, but among the world’s leading experts in my rare eye cancer.

Lately however, I have come back to both Google and social media as sources of medical information, with the proviso that they have to be treated with care and with due attention paid to the identity and quality of sources. So I started seeking an answer to my latest sleep issue. I sensed that the key to my problem was the restlessness which made it impossible to feel comfortable.

Dr Google quickly turned up something called Restless Legs Syndrome. The NHS website told me its main symptom “is an overwhelming urge to move your legs.It can also cause an unpleasant crawling or creeping sensation in the feet, calves and thighs.The sensation is often worse in the evening or at night.”

Yes, that sounded right. But for an answer to my problem I needed a more specialist service, Professor Twitter. Now we all know about the reputational problems that have plagued Elon Musk’s favourite social media platform of choice but those should not blind us to its virtues.

I joined Twitter in 2007 at about the time most of the tech community was gravitating there from Facebook. It quickly became the essential tech newswire, somewhere you could go as a journalist to find stories and contacts. “Anyone know a leading expert on batteries?” I asked in 2008. A couple of hours later I was driving to Bath University to interview a chemistry professor for the Ten o Clock News.

Over the years, Twitter has got noisier and has become one of the leading conduits for misinformation. But I have developed new networks of expertise I can draw on - cryptocurrency experts, transport specialists, bakers, and lately people who are interested in the intersection between health and technology.

So it was to Twitter I turned in search of enlightenment. After mentioning my first bad night, I came back with this after night two:

As you can see, I made no direct appeal for help but I was pretty confident that an expert audience - people with Parkinson’s, neurologists, GPs - would see my tweet and have some advice. And soon the responses came flooding in, both public replies and private direct messages.

Some of this was just people offering sympathy, but there were also practical suggestions:

“Have you tried a weighted blanket?”

“A spray is good, only on the soles of your feet though. Iron supplement also an option.”

“Magnesium supplements have helped me.”

“really sorry to read about your poor night, I'm guessing you've tried rotigotine transdermal patches?”

In the direct messages from physicians and fellow “Parkies” there were several mentioning Parkinson’s drugs. Among them was something I’ve been taking for the last year, Ropinorole, a long-lasting drug I swallow each morning before following up with regular doses of Sinemet.

Suddenly a lightbulb went on. I had been late in renewing the prescription for this drug, so there had been two days when I had not taken it. At the time I had thought the medicine was having little impact anyway so I did not worry about missing it for a couple of days. Those two days coincided with the two nights I had been unable to sleep.

By now I had collected my pills from the pharmacy and had taken my normal dose the morning after my second dreadful sleepless night. I then did something which, admit it, most of us never do - read the leaflet that comes in the medicine box. Way down on the second page came a warning that if you suddenly stopped taking the drug “your Parkinson’s symptoms may quickly get much worse.”

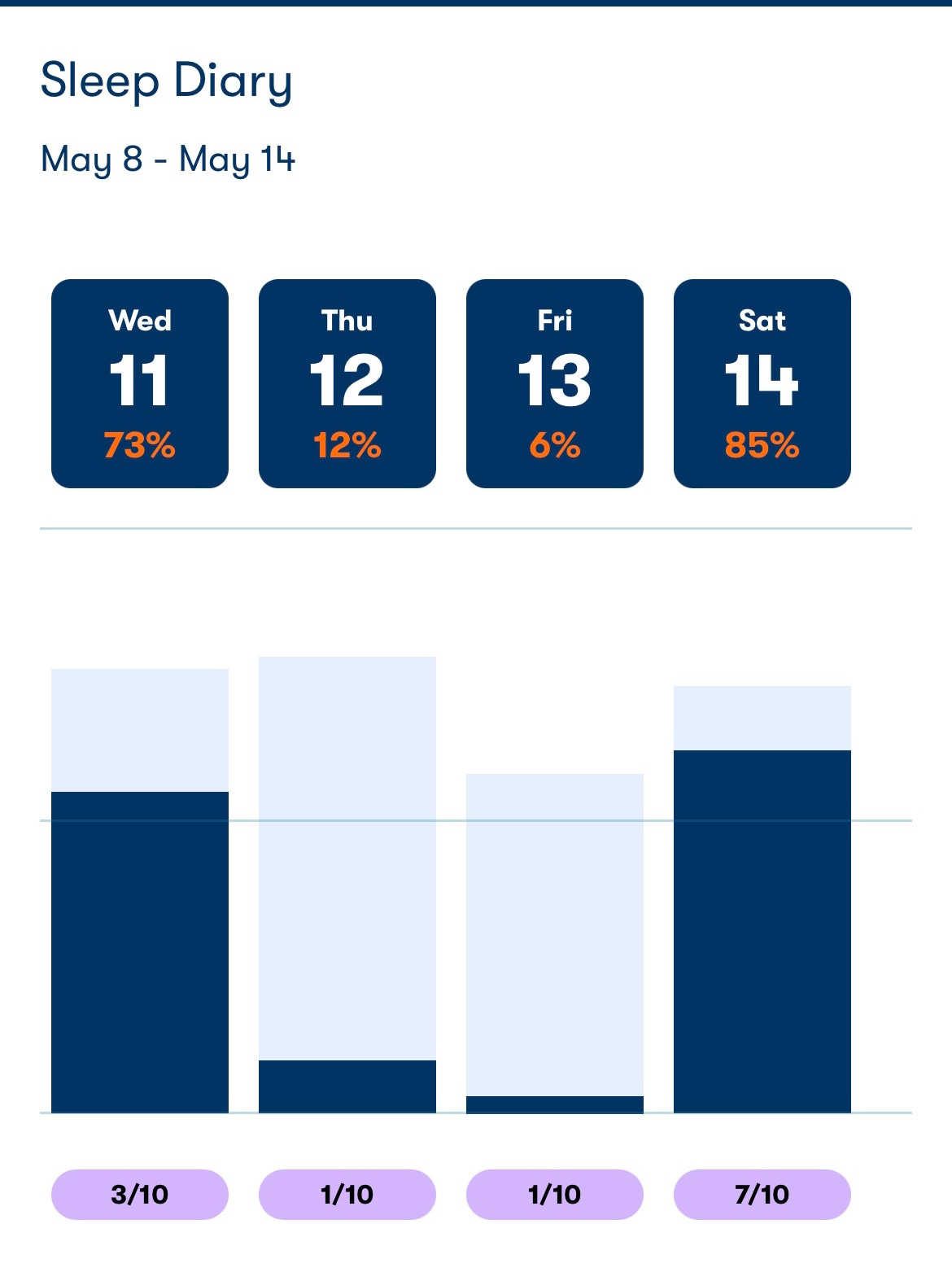

Well, if you consider insomnia to be one of my symptoms that had indeed got much worse. The following night, after taking all my drugs at the right time, I had a solid night’s sleep - in fact one which I was able to rate as “good” in my Sleepio sleep diary for the first time.

Now, remember that correlation does not equal causation, and reading about Ropinorole withdrawal symptoms may have had a placebo effect, lowering my anxiety levels and thus making sleep easier. It is also important to seek out advice from your own doctor when that is available, or to ring NHS 111.

But the informal networks that grow up on places like Twitter can be very comforting - I have found myself both receiving and giving advice about Parkinson’s and ocular melanoma. In 2019 I made a video diary about receiving Proton Beam Therapy for the tumour in my eye. Since then, several people about to undergo the same treatment have contacted me via Twitter and I have been able to talk them through my experience and, I hope, reassure them.

And when it came to my sleep problem, both Dr Google and Professor Twitter showed how valuable they can be - if used carefully. Maybe they too need to come with a long leaflet explaining their benefits and their possible side-effects.

MS support is fantastic on Twitter, searching for the name of a treatment finds loads of people on it, and thus advice and support. Equally helpful with random questions about whether something is a MS symptom or just a run of the mill thing.

There was a fascinating segment on sleep on R4 Start the week this morning, I’d recommend it for a listen.

I must admit that I have never asked for health advice on Twitter. A good part is because like most people, I probably wouldn't get a reply, good or bad, and so it would be a waste of time. I have used search engines, though mostly because I already knew what was wrong and was looking for some extra advice. But for clinical advice, I tend to add "NHS" to my query and hope there is a result from the very useful NHS website.