Why can't the NHS innovate?

Penny's peculiar line may have had a grain of truth

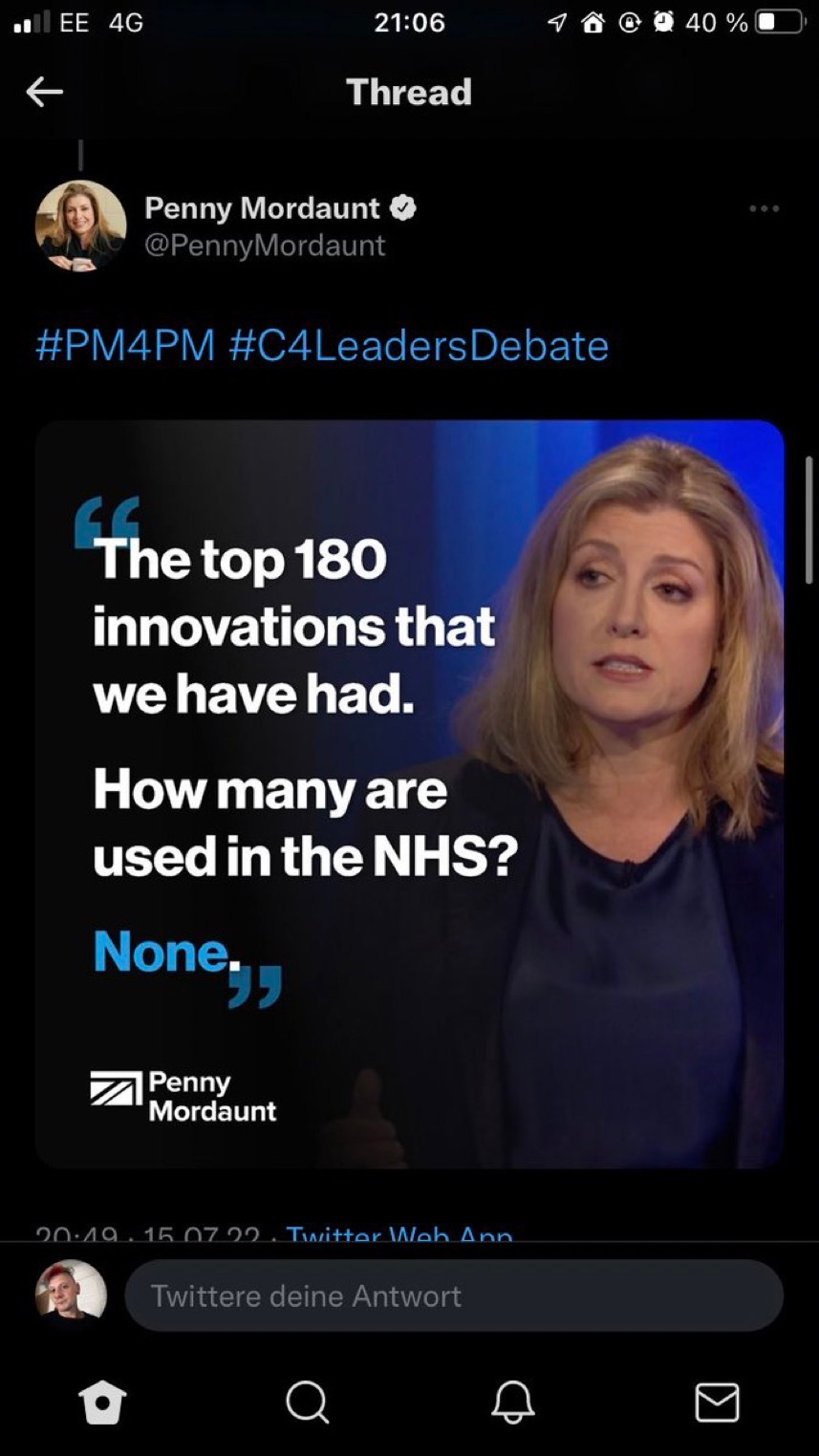

It now seems like an age ago but on Friday night’s Channel 4 debate between the Tory leadership hopefuls, Penny Mordaunt came out with a line about the NHS which was, well…..peculiar. “The top 180 innovations that we have had.How many are used in the NHS? None.”

The Mordaunt social media team liked it so much that they tweeted it out. But people were already asking……whaaat?? Let’s think of some of those 180 innovations we’ve had (and maybe assume we don’t go all the way back to fire or the wheel) and it’s obvious that many of them have been used in the NHS.

The World Wide Web? I’ve definitely seen web browsers on the screens of the computers of my GP and hospital consultants I’ve visited.

Smartphones? They are now being used for everything from remote consultations to symptom monitoring.

Artificial Intelligence? Already being trialled for everything from identifying Parkinson’s to predicting traffic to emergency departments.

Fax machines? Well the NHS was an early adopter and has remained until recently a loyal user of these groundbreaking communications devices.

Ok, maybe the NHS does sometimes feel as if it’s still stuck in the 20th century when it comes to technology - I’ve written about how slow it has been to embrace the kind of scanning systems used for decades in supermarkets. But overall Penny Mordaunt’s sweeping statement about the health service being an innovation desert made no sense, as her social media team seemed to acknowledge, swiftly taking down the tweet.

One influential thinker about the NHS, however, does think the Tory leadership hopeful may have accidentally hit upon a truth about innovation. Axel Heitmueller has spent more than a decade working for a group of hospital trusts in North West London on trying to get the best ideas taken up more widely.

He sounds a little weary: “There's a lot of research that happens,. this stuff sits on shelves, it sometimes gets spun out, it gets into the commercial world, but then it takes years to come back into the frontline service, if at all.” He quotes an old study which says on average it takes 17 years for a discovery to end up with a patient. The team he runs was set up to accelerate that process but he says it’s been tough trying to shake things up. Mind you, he says the problem isn’t confined to this country: “Very few national healthcare systems are any good at this and and that's maybe not surprising, because healthcare is a very risk averse business. It is very hierarchical.”

You might think the NHS was a huge monolithic system where at least managers could hunt out the best ideas and mandate their use by every hospital and GP - but no: “The truth is it's a highly fragmented system that's made up of thousands of individual organisations, and they all make their own decisions.”

So what sort of innovations aren’t happening? Perhaps surprisingly it’s not the whizzy tech and great leaps forward - “the latest blood test that spots cancer” - that excite him but trying to spreading best practice in healthcare that’s been around for years.

He gives as an example treatment of COPD, chronic obstructive airways disease, a major killer but one where the National Institute for Clinical Excellence laid out many years ago a recommended programme of six treatments including help with stopping smoking. “And if you look at the data, are we actually doing them systematically for patients? We're not.”

But in North London, his colleagues came up with a simple idea - send every patient before their next appointment a sheet of paper listing those six treatments with red, green and amber traffic lights signifying whether they had yet had them. The idea was this would empower the patient to ask the GP why they hadn’t been sorted out yet. “I think the role of the public in actually demanding almost best practice is something that we haven't made the best use of.”

Even when it comes to innovations such as artificial intelligence Axel Heitmueller is more keen on what might sound like boring back-office applications rather than AI radiologists or robot surgeons. He suggests for example that there’s scope for devising algorithms to make the use of expensive MRI scanners more efficient: “In London, at any point in time, no one knows how many of these scanners are being used or could be offered to someone who at short notice, the next hour or two, or tomorrow morning, wants to come and have an MRI scan. There's huge scope for just using these sort of algorithms and the kind of data that you have in a much smarter way.”

But when I ask him what single thing would make things better, he comes back to the patient and transparency about their treatment. He points out that we are already becoming more active about our health, recording and storing lots of data on our smartphones and smartwatches, even learning how to carry out simple diagnostic tests for Covid at home. “That's democratisation of healthcare, that's happening. And that I think is where the promising land lies.”

So Penny Mordaunt, if you are reading this, forget about those mysterious 180 innovations that apparently went missing - if you want to modernise the health service, rely on patient power.

The bigger the organisation, the harder innovation becomes, simply because you risk even worse fragmentation of methods than you already have. You can become buried in a plethora of experiments and beta versions.

But there can be (and should be) conflict between people who conduct health care and those pushing new ways of doing it. Bright ideas often sound brighter than they actually are. They might require training, retraining, a change of data types, and yet more training a year in for v2.0. Fine when you are sitting around a desk with a couple of willing testers. But when you are talking about 50,000 nursing staff who need to retrain yet again, your bright idea has just become a brick wall.

There is also a terrible habit of making life harder in the attempt to make it easier. I think here of my aunt's care. She has carers visit 5 times a day.

The most recent agency has been talked into using an online management system by some company. I now get an email to say the carer is on the way, an email to say they have left, and an email asking for feedback - that links to an online form of ratings plus a comment field.

Fifteen emails into my inbox on top of everything else I deal with. And since I don't live at my aunt's, and she has dementia, there is no way I can fill out the feedback form. So I don't.

But if I and everyone else did fill out the form, (including the carer who is meant to list everything they just did), the little care company then gets deluged by data.

And it creates data holes. What happens if someone forgets to fill out a feedback form? Does that mean they were too busy? That the care was so bad they were speechless? It was fine so they didn't bother? You always know why someone feedbacks data, but you never know why they don't unless you spend even more time to chase them up and ask them, which might not be welcomed.

This is innovation, but it is bad innovation. And as much as the NHS and other orgs might be slow in taking on new ideas, there is a long-standing set of good reasons why they are sometimes cautious. They have been sold far too many sow's ears or ended up with brand new systems that are dated within a year and they have to buy another one.

The NHS MUST focus on care first, and look at innovation second. And the reason is the patient. If nothing else has come clear over the last 1/4 century of IT innovation in the NHS, by far the best care still comes from wonderfully analogue interactions between clinical/caring staff and the patient.

And with that often weakened by staff shortages, that must come first. There isn't an app that can truly replace a therapist sitting down with someone and showing them how to cope with something.

Here's a few elements of innovation and their impact on health, AHSNs were setup for this purpose:

https://www.easternahsn.org/healthcare-provider/impact-stories/