How often do you think about how you walk? My guess would be very rarely - unless you have Parkinson’s. For many “Parkies”, problems with walking were an early sign that something was wrong - I kept dragging my right foot - and we measure the progress of our condition by keeping a close eye on how easy it is to go for a stroll.

So when I was invited to take part in a clinical trial which involved a close examination of how I walk I leapt (or should I say stumbled) at the chance. The trial took place at VSimulators, a University of Exeter lab which can simulate all kinds of environments and uses motion capture technology to record movement.

A team led by psychologist and expert in rehabilitation Dr Will Young wanted to look at a phenomenon called freeze of gait, where people with Parkinson’s suddenly find themselves unable to move, and examine a strategy they have devised to deal with it. They needed three sets of participants - people with Parkinson’s who suffer from freeze of gait, Parkies who don’t, and people who don’t have the neurodegenerative condition.

I fall into the second category - I dread the moment that my friend Paul Mayhew-Archer describes where the tube doors open and he’s unable to move, missing his stop, but it hasn’t happened yet.

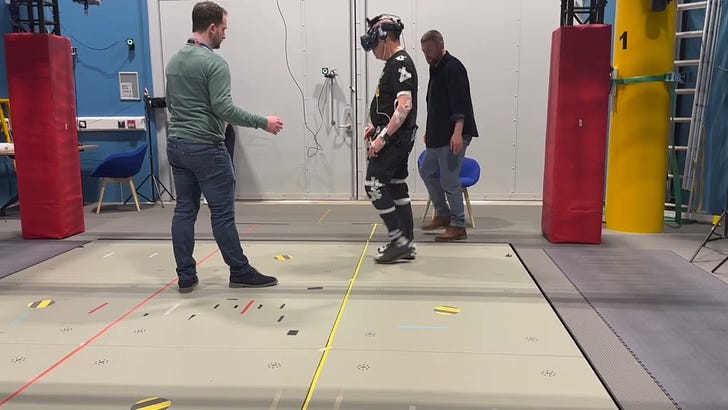

The difficulty that the Exeter researchers have is actually being able to record a freeze as it happens. They showed me one of the techniques they use on the moving platform in the lab, simulating a sudden halt on a train. Then they got me ready for my close-up, sticking 36 sensors all over me so that my every move could be captured.

I was then asked to walk slowly through a sequence of turns on a pattern laid out on the platform before putting on a virtual reality headset and going through the same sequence. This time I was walking through a series of doors in a virtual home with clutter on the floor and garish paintings on the walls - apparently just the kind of thing that can bring on a freezing episode.

While that didn’t happen to me I was very conscious of my dragging right foot and felt I was walking badly, so I was surprised to hear afterwards that my gait was relatively normal.

What the whole trial is about is testing a method people might use to unlock a freeze. I had assumed that this must involve some kind of technology like the cueing devices I’ve been testing. But no, the Exeter team have developed a mental technique.

“When we start walking, we need to shift our balance in a way that puts us in the right position to take the first step,” Will Young explains. But people who experience freezing of gait have trouble getting started again. “We think this is because the ‘set of instructions’ the brain creates for the weight-shift & step combination becomes less clear. There are several parts to these instructions, but the current Parkinson’s UK trial involves people being trained to use a simple mental strategy designed to replace processes that do not work as well and put people in a stronger position to make the first step from a freeze.”

I have to say that this still isn’t very clear to me, except that it seems to involve creating a mental image in your brain that shows you moving - then it happens. But Jane Rideout, the inspirational Parkie who had lured me down to Exeter for the day and acted as my chauffeur, insisted that the technique was “screamingly obvious.” She does suffer freezing of gait and had taken part in the trial, finding the mental strategy worked for her.

Early results from what is a preliminary study showed that the strategy did help many of the 72 “freezers” who took part unlock. The next step is a more ambitious trial getting people to try out the technique in their own homes. This will start next year but Dr Young is inviting anybody with freezing of gait who is interested in taking part to contact him via his university email address.

What strikes me about this kind of trial is that the very act of being asked to think about how you walk may have an impact - either positive, like the placebo effect of taking a sugar pill, or negative as you become more stressed. Certainly, a lot of Parkinson’s is quite literally inside your head in that it is caused by physical changes in the brain while the symptoms can be worsened by anxiety and stress.

But I came away from my day at the walking lab feeling upbeat. Large sums are being poured into research into new drugs, far less into other ways of treating Parkinson’s, so it is encouraging that Parkinson’s UK is funding this project. One highlight of my visit was meeting a young sports scientist whose PhD was all about examining exactly how people with Parkinson’s turn while walking. If such detailed study helps people cope with one of the condition’s most distressing symptoms then the charity’s money will have been well spent.

Dear Rory

I had freeze of gait so badly and so often that it was a major factor in the choice to move to a care home – where, contrarily I have it very infrequently. The only link I could see to the environment was less freeze of gait when I rinsed my floors which is very odd

Best wishes David Satterthwaite

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Professor David Satterthwaite

Research Associate, Human Settlements Group

Editor, Environment and Urbanization

International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED)

Third Floor, 235 High Holborn, London, WC1V 7LE | T: +44 (0) 7731 777785

E-mail: david@iied.org Twitter: @Dsatterthwaite