It was a technology which in under two decades spread from 150,000 hobbyists to over 38 million households. Its arrival transformed the way we lived, bringing the world into our homes, connecting us with politicians, sports stars and musicians. But it also brought anxiety about its impact on the family, in particular on young people, and whether the technology was so addictive that it stopped us communicating with each other.

No, I’m not talking about the internet or smartphones but the first communications revolution affecting just about everyone, the arrival of radio in the home just over a century ago. A visit to a fascinating exhibition mounted by Oxford’s Bodleian Library, Listen In: How Radio Changed The Home got me thinking about the way new technology is always greeted with a mixture of excitement and dismay.

The exhibition is about the period from the birth of the BBC in 1922 until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, seventeen years in which the British public went from viewing radio as some sort of magic trick to the ever present soundtrack to home life.

I was fortunate enough to have a guided tour by the curator of the exhibition and author of the accompanying book Beaty Rubens, who has had a long career as a very distinguished arts radio producer and also happens to be a dear friend.

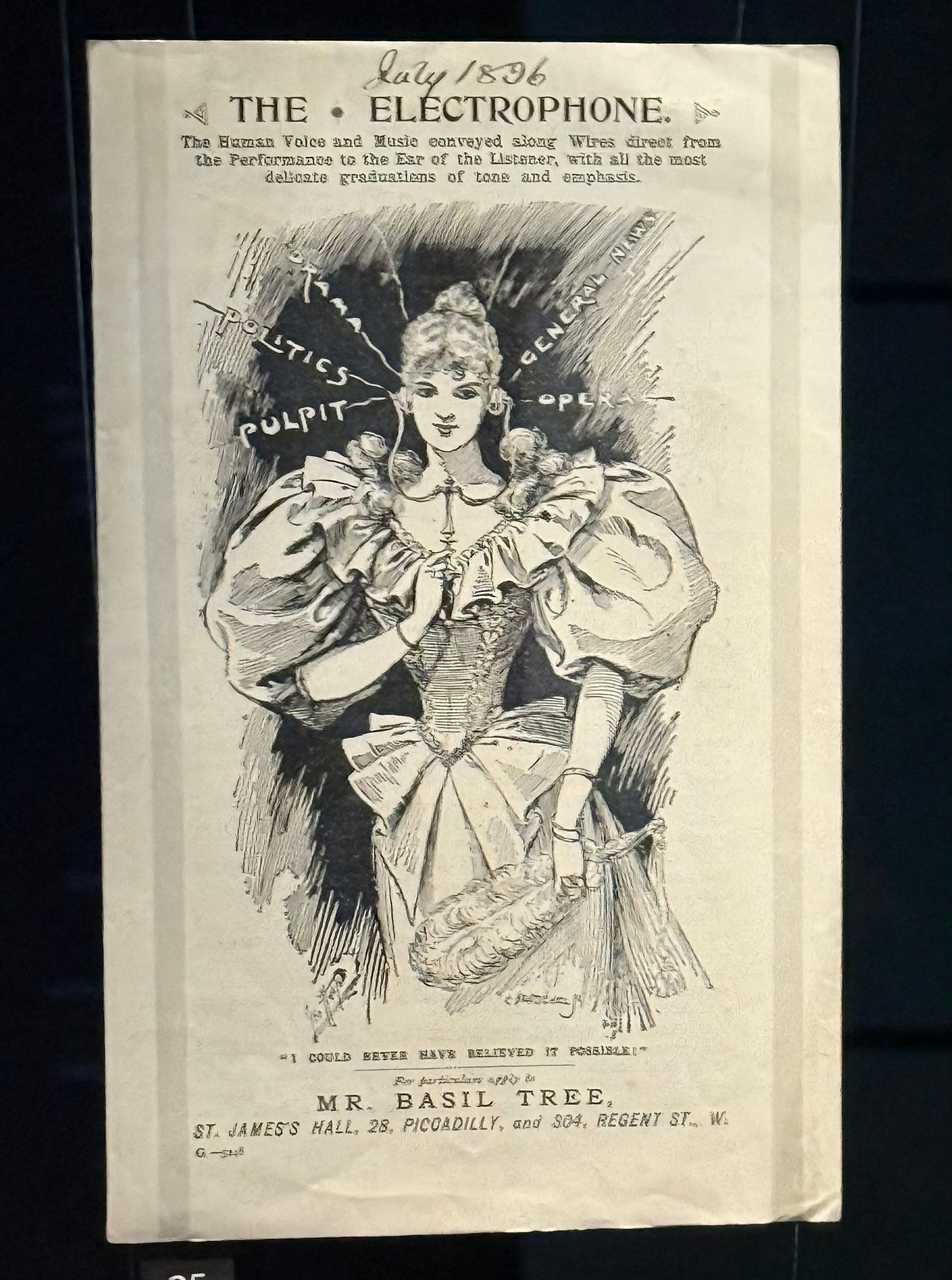

Beaty set the scene by explaining the role of the Titanic in getting the public used to the idea of the technology, with Marconi’s wireless telegraph equipment making it possible for ships to come and save 700 souls from the stricken liner. We also heard of the failed experiments that preceded the arrival of radio, like the service which saw concerts and talks broadcast down the telephone. As it meant you needed two phone lines at a time when only the wealthy had a telephone that was never going to fly.

When radio arrived there was soon a wide range of devices to fit most pockets, from the “cat’s whisker” sets built by hobbyists to stylish radiograms costing the annual salary of a junior teacher.

And as broadcasters experimented with this brand new medium some ideas worked better than others. I loved hearing how sports commentators described a game by referring to a grid printed in the Radio Times to show listeners where the ball was. Apparently, this is where the expression “back to square one” originated.

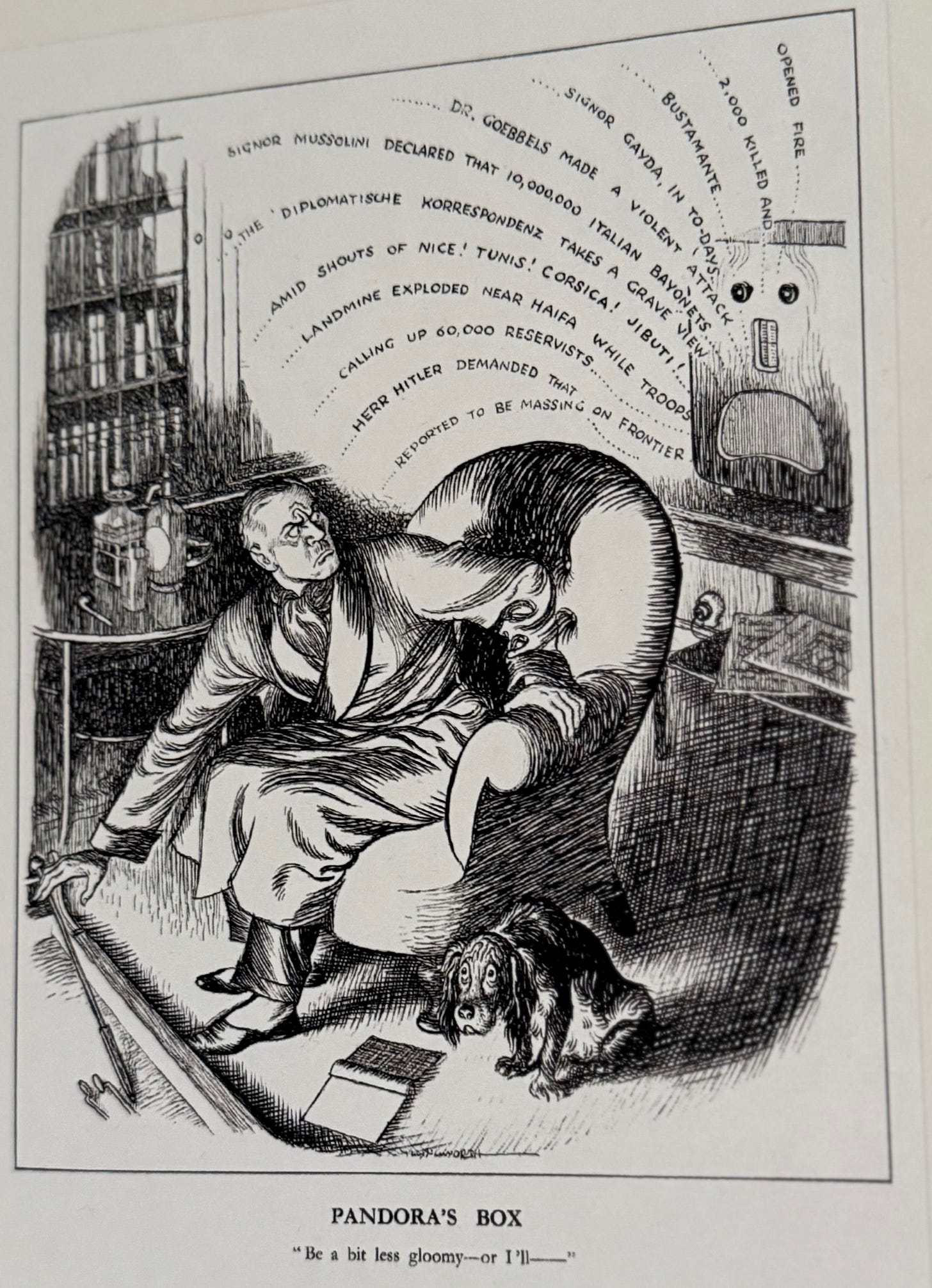

The anxiety about how the new technology is affecting human behaviour is highlighted in cartoons which will strike a chord with anyone who worries about the same issues today. One shows a listener tormented by the constant stream of bad news coming out of his radio and wanting to tune out.

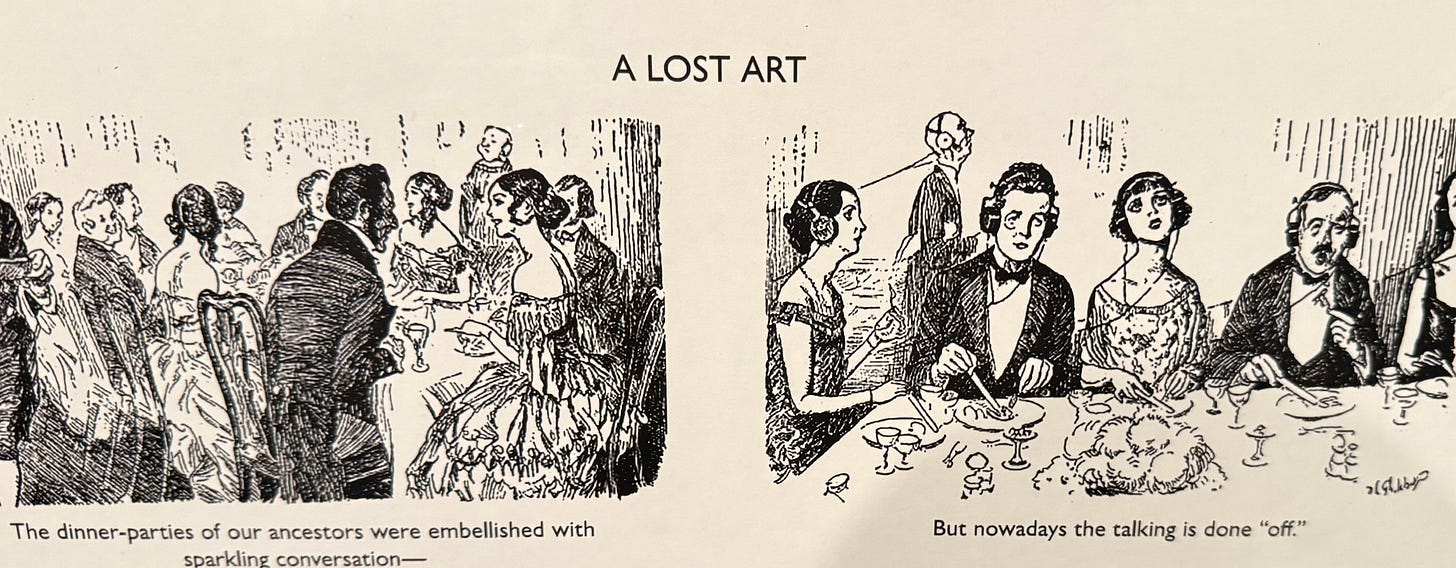

In another entitled A Lost Art a jolly gathering around the dinner table is contrasted with diners all apparently absorbed in listening via headphones to the radio rather than talk to each other.

There is much more, including readings by actors of interviews in a 1930s survey of listeners - the wife whose tyrannical husband is in sole control of the radio and forbids her to listen when he is away, a grocer so obsessed with the news that he says he fears he’s neglecting the bacon slicer.

I came away wondering whether the radio revolution was actually a far more transformative experience for those who lived through it than the rise of the internet or the arrival of the smartphone. Do go and see the exhibition which runs until August 31st.

I have rather snootily talked to my grandchildren about how I grew up in a world without screens, but I completely failed to imagine a world without radio. Oh dear.

If I were to live on a unnhabited island I could do without television, the internet and a smartphone but never without radio.