Sonia Gandhi: Mapping the Parkinson's Brain

I wrote recently about my visit to the Francis Crick Institute where I learned about an exciting plan to accelerate clinical trials for drugs which might halt Parkinson’s in its tracks. But the main purpose of my visit was to try to get a grip on the work Professor Sonia Gandhi and her team are doing on mapping what happens inside the brain of someone who has Parkinson’s.

Knowing just what causes the loss of dopamine-producing cells in the brain is vital if we are to find ways of halting or reversing the progression of Parkinson’s. But despite many years of research Professor Gandhi says until recently only the fuzziest of pictures had been produced:

“It's a bit like the lowest density Ordnance Survey map. It contains so little information - it tells you where the neurons have died but nothing more.”

Three years ago I visited the Parkinson’s Brain Bank at the Hammersmith Hospital where they examine the brains of people who have died with the condition, having agreed years earlier to become donors. While the team at the Crick use some material from this and other brain banks, they also want to look at what is happening at a much earlier stage in the development of the condition.

“We're quite interested in looking at the first things that change in the brain. And so we have to find people who have died of another cause early in their Parkinson's journey, which means that we have their brain in such a state that the Parkinson's is at an early stage.”

But much rests on a vast improvement in imaging techniques allowing researchers to look at the brain in ever finer detail. Until recently, Professor Gandhi explains, they were taking a slice of brain, and perhaps getting some interesting readings but not knowing exactly where that was coming from. “Whereas in the last five years, medicine has been totally changed by something called single cell technologies.”

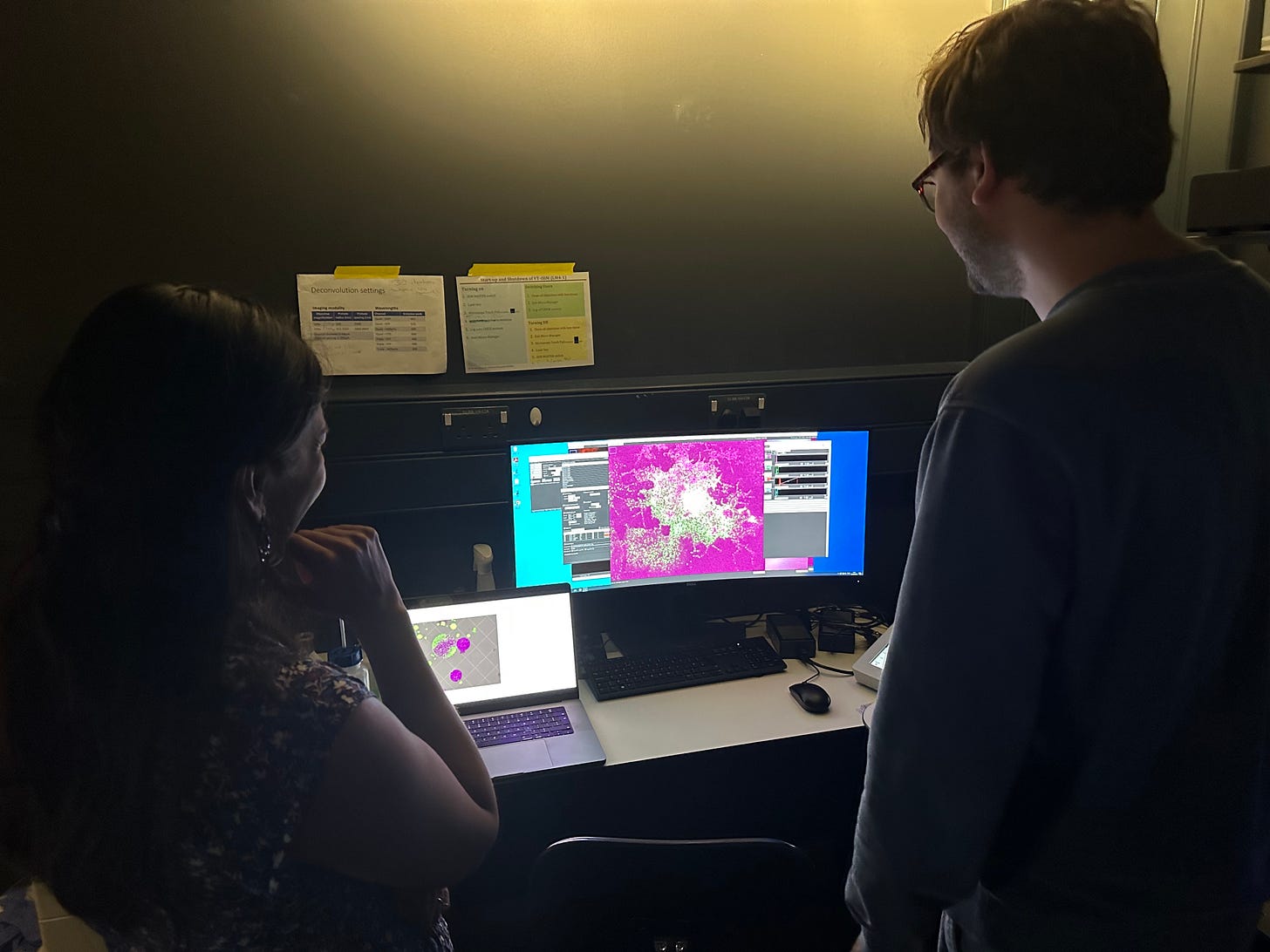

She takes me upstairs to a room housing the extremely powerful microscopes which make this possible: “Every single cell, neuron by neuron, goes through a droplet, and then we measure all of the genes expressed in that cell.” And if they can get hold of brains of people who have died when their Parkinson’s is at an early stage then they can get closer to the origins of the condition:

“So now we're not looking at big things that are happening at the end of Parkinson's, we're looking at the very first things that happen inside the human brain.”

Of course the big problem is that, whereas with cancer researchers can examine the tumour of a living person to understand what is going on, they are only able to look deep inside the Parkinson’s brain after the death of the patient. But the Crick team has a plan - to build a model. Not of the whole brain - that would be far too complicated - but of an individual brain cell:

“Having a model puts us in a very powerful position because we can try out things,” says Sonia Gandhi. The model allows them to conduct experiments for instance with drugs and make predictions about whether they would work in a trial. “So for example, in our cells that we've made from patients, we've tried exenatide,and we've been able to say well, actually, in the midbrain neuron, exenatide is doing this, this and this, And that's what we think it's doing in the human brain when it reaches there in the trial setting. So models are really powerful.”

Real outputs then from what at first feels like blue skies research. But this is a complex programme generating vast amounts of data and it is a hugely expensive. business. So it is fortunate that the work being done by Professor Gandhi and by her colleagues at UCL is being supported by the world’s most generous Parkinson’s philanthropist. Google co-founder Sergey Brin, who has a genetic mutation which makes it likely he’ll get the condition, is thought to have donated more than $1 billion to Parkinson’s research and $27 million of that has been awarded to UCL.

We in the UK cannot summon up funding on that scale - the excellent Cure Parkinson’s has.put £16 million into research over a period of 17 years. But thank goodness we have scientists of the calibre of Sophie Gandhi, able to demonstrate that cutting edge research which is unlocking the mysteries of Parkinson’s is happening this side of the Atlantic and is worth funding.