Every now and then my fellow movers and shakers indulge me by allowing me an episode about technology. They stifle a yawn when I bang on about new gadgets that could change the way Parkinson’s is treated and I can see them thinking “here he goes again”. But then when we record in the pub, they find themselves enthused by the visions of a hi-tech healthcare future that our guests sketch out.

That at least was how it turned out this week when we learned about how AI could speed up the diagnosis of Parkinson’s and a smartphone app could allow doctors to have a far more detailed view of a patient’s progress than they get from an annual hospital appointment. But we also asked whether the NHS is ready to invest in this kind of innovation.

Our first guest was someone I had met in December at the recording of the Royal Institution Christmas lectures, which were all about artificial intelligence. Dr Rutger Zietsma was there to demonstrate one use of AI in healthcare - a pen which can diagnose Parkinson’s by analysing the user’s movements as they write and draw - and I was the guinea-pig.

In the pub, that role fell to Gillian Lacey-Solymar. Dr Zietsma asked her to use the Neuromotor Pen, developed by Edinburgh-based Manus Neurodynamics, to trace circles on a tablet computer, one of a number of exercises that a patient would complete in a genuine consultation.

“Drawing is one of the most complex, fine motor skills that humans are capable of performing,” he explains. “It's a learned skill, and it's a skill that typically deteriorates as we get older.”

But conditions which impair the brain such as Parkinson’s also affect our ability to draw:

“From these measurements that we're taking from this pen on the tablet, we’re understanding how these impairments affect somebody's movements, and therefore we can first of all quantify symptoms with very high precision, but also we can differentiate between different movement disorders.”

The neuroscientist says part of the problem with the tricky process of diagnosing Parkinson’s is that someone with a shaky hand could have essential tremor, a less serious condition. So at first sight, the doctor may not be able to decide what they are seeing, necessitating further appointments and a long wait:

”If you can increase the accuracy of the first appointments from let's say 50% to 80%, that can give you a slightly earlier diagnosis. And instead of seeing a patient a number of times over an 18 month period, you may be able to make the diagnosis early on. “

Where the AI comes in is in identifying patterns in the data generated by the pen which can be ascribed to different neurological disorders. Dr Zietsma thinks this could be particularly useful for GPs trying to decide which patients to refer urgently to a consultant neurologist. Given that the Movers and Shakers’ Parky Charter sees speeding up that first visit to a specialist as a number one priority, we can clearly see the potential of the Neuromotor Pen.

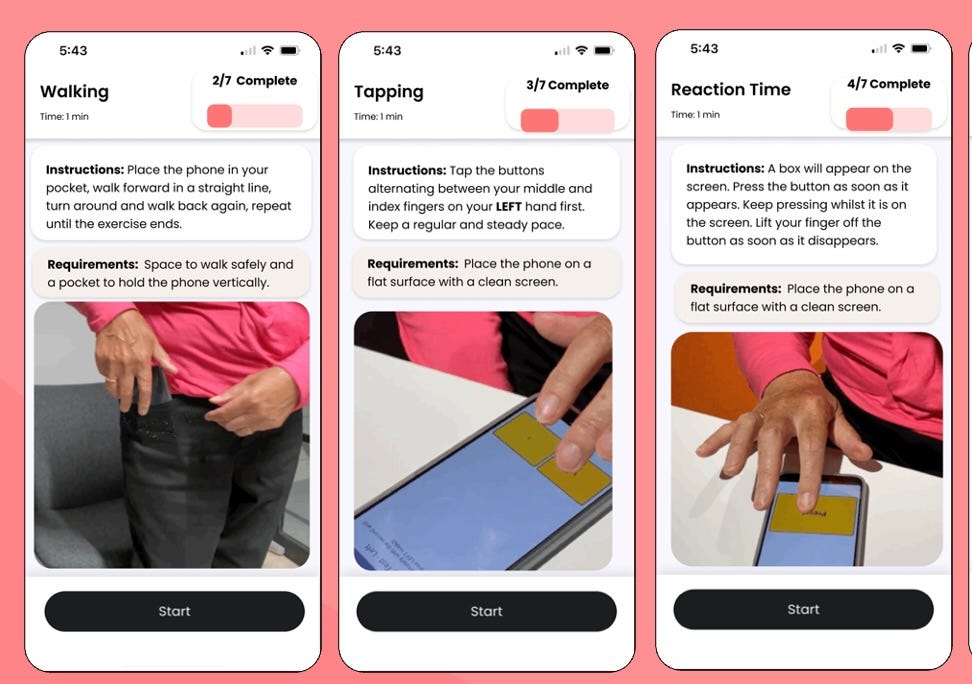

And our second guest Caroline Cake, Chief Executive of Neu Health, also has a project which could help improve care. It is an app which uses a smartphone’s sensors to enable the remote monitoring of people with Parkinson’s between hospital visits. I have been trying out the app which first requires the user to go through a series of exercises four times a day for a week - saying “aaahhh” into the phone, walking up and down with it in your pocket, tapping with alternate fingers on the screen while counting back from 100, and so on.

All of this data is then uploaded to the cloud and analysed using algorithms developed by two Oxford research labs to assess your current symptoms and how your Parkinson’s is likely to develop. By asking the user to record when they take their medication, the app can also help doctors give more timely advice: “They can actually see are you on the right medications, are you adhering to them appropriately, do they need to adjust anything in your care?”

Instead of the annual appointment when you are asked how the tablets are working and the dose is then tweaked and its effects not checked for another year, Neu Health promises constant monitoring and treatment built around the individual. The result, says Caroline, should be fewer routine hospital appointments for those doing well, but more timely treatment when a patient’s condition is deteriorating.

What I found striking about both of these projects is how long they have been in the making. Rutger Zietsma began thinking about his Neuromotor Pen while working on his PhD at Strathclyde University more than a decade ago. Neu Health builds on years of research by two eminent neurologists Michele Hu and Masud Husain,

Neu Health’s app is currently being trialled by NHS Trusts in Suffolk and the Neuromotor Pen has been designated a “Breakthrough Device” by the FDA, an important step on the path to being cleared for use by the American medical regulator. Yet both are still some way from moving out of the startup phase and becoming profitable companies.

And although neither will say it, the concern is that these two British companies are most likely to find that their route to profit lies outside the NHS. At a recent off-the- record seminar one leading UK healthtech company told me they had almost given up on their home market - NHS Trusts were keen on short-term pilots of their products but did not want to commit to any serious investment, whereas in the United States they were finding plenty of eager customers.

As we discuss what we have learned at the end of this episode, Nick ‘Judge’ Mostyn makes the good point that both of these companies are generating huge amounts of valuable data which should help in the effort to understand Parkinson’s, and Mark Mardell expresses the hope that technology like this will save the NHS money and give it a more secure future.

But Gillian Lacey-Solymar, a successful businesswoman who has lectured on entrepreneurship, feels she has. spotted a familiar pattern in the UK: “I just worry about this country not adopting the technology fast enough…. We're brilliant at innovation and then we're not good at rolling it out. Tragic, really>”

And Jeremy Paxman who, as so often, has started sceptical but ended up captivated by what he has heard, sums it all up:”It breaks my heart to think that people aren’t taking advantage of something that has been developed here.”

Let’s hope that Jeremy is being too gloomy. After all, there is some evidence that world-class Parkinson’s research in UK universities is now being spun out into ambitious young companies led by a new class of entrepreneurial scientists. We will keep an eye on projects like the Neuromotor Pen and Neu Health and report back on their progress.

Some exciting news this week - Movers and Shakers is among the nominees for the Broadcasting Press Guild’s UK Podcast of the Year award. The winner will be announced on March 21st.

Extremely interesting on many levels not least regarding the care, treatment & diagnosis of Parkinson's. The poor record of tech investment in the UK is very concerning & yet another example of short termism.

I say this as a parkinsons nurse, we are able to review people much more frequently than a once a year neurology appointment. We can monitor medication change, discuss problems and refer to physio or speech therapy and encourage people to contact us at any point to discuss concerns.