Movers and Shakers: Pumps

A new way of getting your dopamine drugs

It has not been a great autumn for people hoping for a cure for Parkinson’s, by which I mean a treatment that can slow, stop or reverse the condition. All eyes have been on Exenatide, a diabetes drug which has been going through a phase 3 clinical trial after showing great promise of slowing the progression of Parkinson’s in previous trials. But at this week’s Cure Parkinson’s Research day the man leading the trial Professor Tom Foltynie confirmed the news that had been given to trial participants a few weeks earlier - the drug had failed to produce the results achieved at phase 2. After 16 years of testing, the Exenatide story had not had a happy ending.

But while the search for the first disease-modifying drugs continues, Movers and Shakers is this week dedicated to an innovation which can’t slow or stop Parkinson’s but can apparently make many of its symptoms disappear. Suddenly, pumps that can deliver drugs into the body in a steady stream seem to be all the rage.

But our special guest Professor Ray Chowdhuri, Nick “the judge” Mostyn’s neurologist and long-term friend of the podcast, tells us that they are nothing new:

“We've had experiments with pumps in Parkinson's from the 1970s really, and it was all based on the fact that pumps give dopamine in a standard, what we call continuous fashion, whereas with tablets, you get a ‘pulsatile’ delivery, you have the peak and then the trough. And that's not the way the brain likes its dopamine. The brain likes its dopamine in a very standard, continuous fashion.”

The trouble was that the early pumps were very bulky and there were problems finding the right drug to work with this technology. But now the pumps have become much more compact and it has been shown that with the right drug combinations they can deliver spectacular results.

Many of us had seen a video in which Damien Gath, whose Parkinson’s was diagnosed 12 years ago, was shown first shaking violently as he tried to make a cup of tea, then, with a device attached to his belt, suddenly completing the task without any problem. He was one of the first people in the UK to be given Produodopa, a combination of foslevodopa and foscarbidopa, through a pump with a cannula sending the drugs more directly to his brain.

In February, NHS England announced that the Produodopa pump would be made available to “hundreds” of people with advanced Parkinson’s.

Then in July, the NHS approved something called LECIG , a gel which combines Levodopa, Carbidopa and the enzyme blocker Entacapone and is delivered by a pump direct into the gut.

Professor Chaudhuri has been working with Produodopa and is very pleased with the results:

“I've had at least two people now able to return to work, and also their carers have gone back to work. So it's quite a dramatic difference.”

And Gillian Lacey-Solymar has spoken to her friend Jan Fuller, who is hugely grateful that she has a Produodopa pump:

“My life has changed totally. It's almost a miracle drug,” she says. Jan admits there are challenge - the daily routine of having to change the infusion syringe every 24 hours, the care that has to be taken to avoid infections. “But the challenges of it and looking after it are nothing compared to the benefits it has delivered to me. My life has changed, and I actually have a life and potential future .”

It sounds wonderful - and it appears likely that thousands of people with Parkinson’s will be badgering their consultants to get them a pump. But this is where brutal NHS economics come in - bringing in this new treatment involves quite a lot of investment in staff and infrastructure. At the start, patients may need help every day in getting the needle in properly and avoiding the skin irritation that is a common side-effect.

It seems that NHS England has budgeted for only around 1,000 people with Parkinson’s to get the Produodopa each year. One neurologist told me that even that target may be hard to hit as hospital trusts have been slow to find the staff needed and prepare them to work with this new approach.

Towards the end of the podcast we pivot to another subject, with Professor Chaudhuri telling us about the new initiative he is promoting in the UK and around the world to get neurologists to think more broadly about Parkinson’s. He is concerned that too many doctors just put their patients on Levodopa and fail to tell them about other aspects of their condition - the importance of a good diet and plenty of exercise, the non-motor symptoms such as depression or poor sleep.

He gives as an example the importance of taking your drugs on an empty stomach and not eating any protein for 40 minutes afterwards - and in particular avoiding dairy products and that includes milk in your coffee.

“Simple advice, but I'm shocked to see that it is never given almost in clinics, and then people would come in the clinic and say ‘Doctor, my leverdopa tablet is not working.’ ‘Okay, let's go up one dose.’ Well, no, just see it is being taken properly.”

Another example he cites is that 1 in 2 women and 1 in 5 men over 50 with Parkinson’s will have osteoporosis and so should be extra careful to avoid falls. A simple test could alert people to this risk.

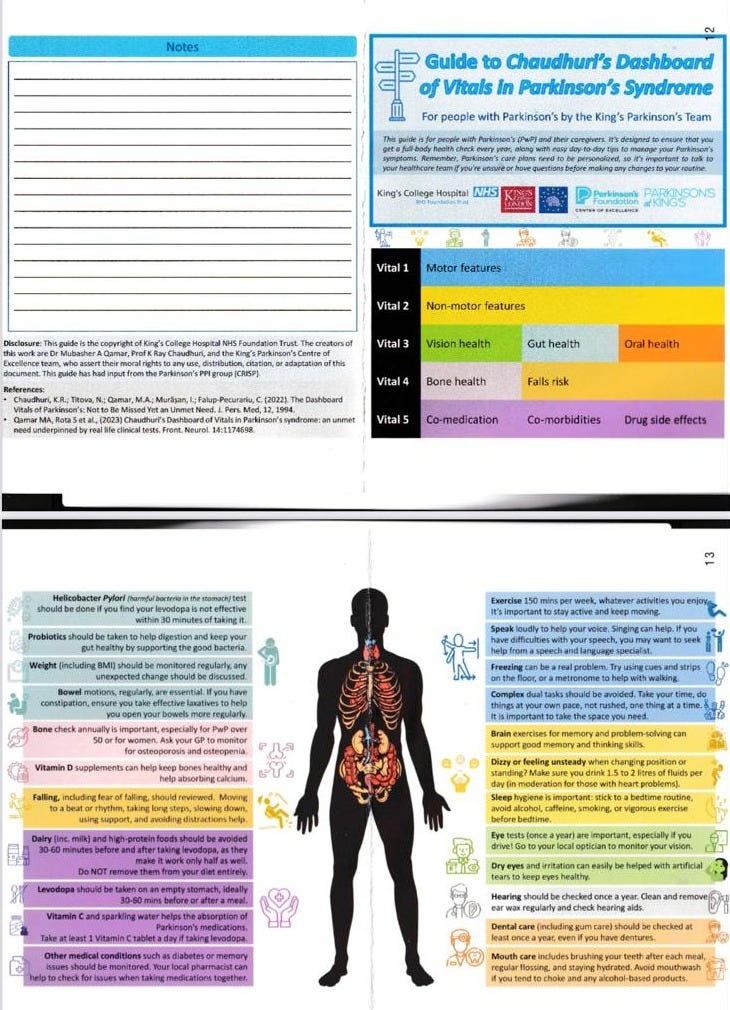

The Prof’s solution is what he calls a dashboard, a simple checklist for doctors and nurses to remind them of what they need to ask in the clinic. He also sees it having a wider audience:

“We would like very much the patients to have it so they can download this in their phones, perhaps when they go to see a doctor, remind them. Doctor, I haven't had my bones done..”

What strikes us is that it is quite worrying that neurologists are not doing these sort of checks anyway. He says they face ever greater time pressure:”You are under increasing pressure in. NHS, you have only 10 or 15 minutes. You cannot remember everything. Well, here's your prompt to make sure you do these things.”

Professor Chaudhuri is now keen to turn his dashboard into a simple phone app, but doing that and then marketing it to doctors and patients will cost money. To that end, he and Nick Mostyn have set up a charity to raise awareness of what the neurologist calls the hidden iceberg of non-motor Parkinson’s symptoms, with the dashboard playing a major role in this campaign. It is called King’s Parkinson’s and you can read more about it here.

I was struck by the point about tablets giving a peaks and troughs delivery. I take 3 Co-Careldopa each day and I imagine that's probably a common prescription. But I also have a prolonged release Sinemet when I go to bed to help reduce the risk of falls when I get up in the night. Why not make all the tablets prolonged release to reduce the peaks and troughs effect? Maybe the Sinemet costs more but I'm pretty sure it will be less than the cost of a pump. Anyone able to comment?