Is the NHS app the answer to everything?

Not unless someone gets a grip of the health service's digital direction

Back in 2018, in the digital dark ages when video appontments and even texts to patients were seen by many doctors as radical and dangerous innovations, I went to interview the then Health Secretary about a bold new initiative.

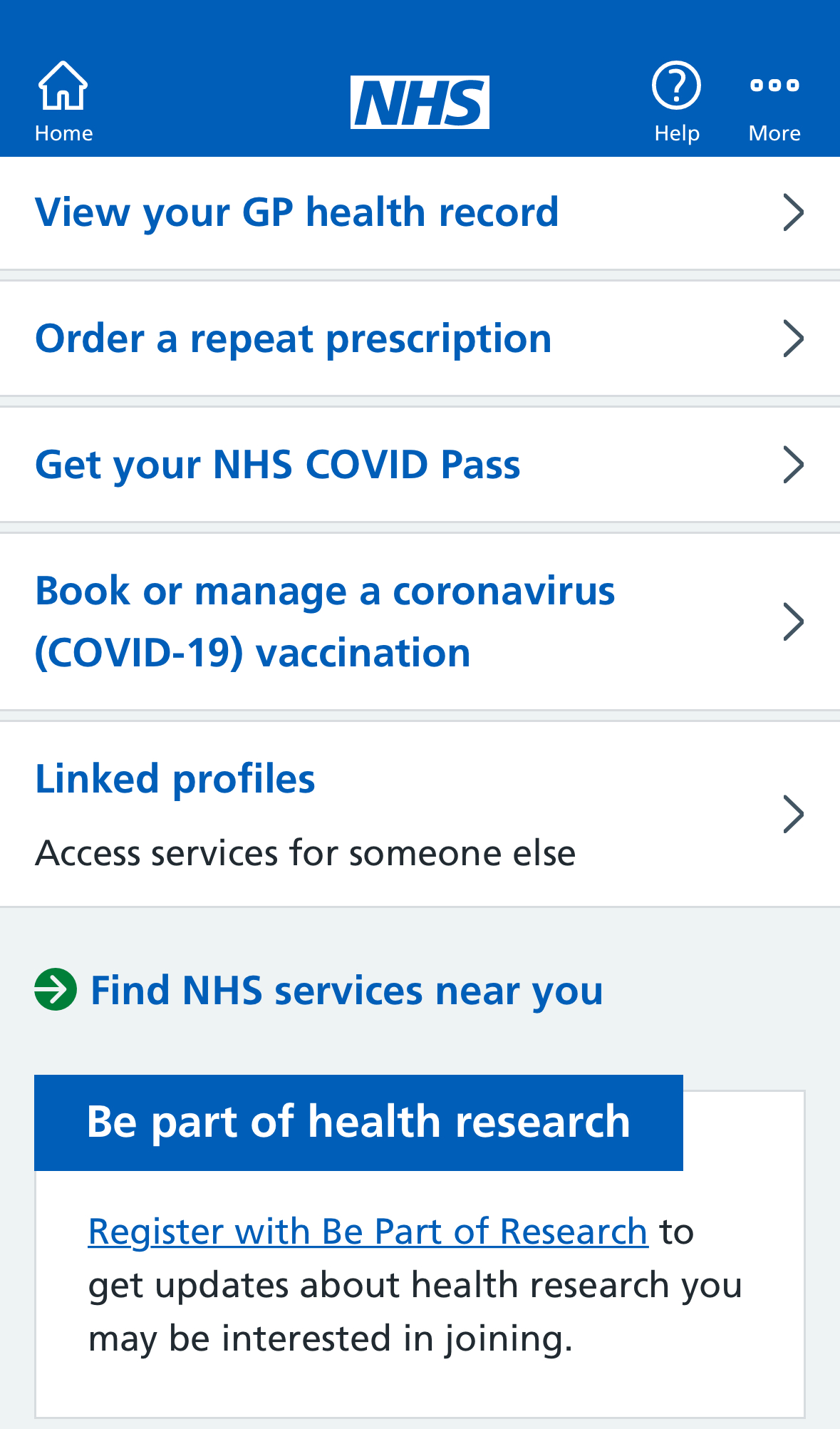

Jeremy Hunt showed me something that he said would be part of a technology revolution sweeping through the NHS, giving patients more control over their healthcare. It was called the NHS app and it would allow us to book appointments and repeat prescriptions and get sight of our patient records - surely everbody would want it?

But the app got a lukewarm reception from GPs, their Royal College warning of the need for support for practices rolling the app out and expressing concern about security. And as for patients, well they showed only moderate enthusiasm - certainly compared with the reception for another app launched in the UK in the autumn of 2018, TikTok.

But Covid changed everything. In March 2020 only around 3 million people had downloaded the NHS app, then it was used to host the vaccine passport required to check into pubs and restaurants as lockdown eased and then to get on a plane and travel abroad. That saw downloads soar to 30 million.

Now there is talk of the NHS app playing a much bigger role as a one-stop shop for patient information. That sounds like a good idea to me. From having little or no online engagement with my doctors I’ve now got almost tooo much - my GP sends text messages about appointments and has an online platform where I can order repeat prescriptions, and the various hospitals I visit each seem to have different platforms to keep me informed each with their own password.

Amongst the changes being trialled are booking a vaccination via the app, using it as a platform for online consultations and giving people more comprehensive access to their patient records from hospitals as well as GPs.

I’ve spoken to two people who have been intimately involved in NHS digital services to see how they see the future of the NHS app. Chris Fleming, now at the consultancy Public Digital actually ran the app for a year as programme director, joking ruefully that he left just before the Covid Pass turned it into a monster hit. Axel Heitmueller was involved in all sorts of Covid projects and works for Imperial College HealthPartners, an innovation consultancy that's owned by the NHS.

Chris admits that while there were big ambitions for the NHS app when it was launched it had proved difficult to get any momentum behind it before Covid: “It actually risked languishing until that moment where the pandemic came,” he says. But he now believes there is a great opportunity to bring a patchwork of digital services together: “I think users are terribly confused about the offers out there and having an NHS approved experience that's ties things together for them is generally a good thing.”

But he has concerns about the integration that will be needed with the major software systems used across the NHS: “If I want to use the NHS app to check my hospital appointment, I need it to integrate with whatever software system is being used in my local hospital.” He says that will be tough: “In my experience, the levers we have to influence some of those software providers and to make sure that the experience is a good one can be limited.”

Axel Heitmueller agrees: “The fundamental problem of digital in the NHS is interoperability.” But he is sceptical about any grand plan to get the giant software companies that compete for NHS contracts to play nicely together. “I think that's doomed to fail and we have never managed to do that even with a relatively small number of GP systems.”

But he does see an opportunity for patients to be what he calls the integrators of all this health data trapped within all of these incompatible systems: “What I would love to see is a requirement for every care provider, whether they're in the NHS or your dentist or whatever, to have a duty to publish into your patient care record some information about that interaction.”

And he says patients would probably end up improving the quality of the data which ended up in what he calls a Citizen’s Account because they would be better placed to spot mistakes. But Axel seems dubious that the still very basic NHS app is well suited to do this job - “it's not an app it's basically a website on a phone” - and he has a much bigger concern.

He says that as the NHS tries to go digital it lacks a basic operating principle, an ability to describe how it wants to deliver services: “The stuff that becomes digital is just taking pretty poor processes and switching them from analogue to digital, rather than using the power of digital to have a very new way of delivering services.”

More poetically he describes the NHS as a directionless orchestra which can’t decide which piece to play: “Everyone is just rehearsing in their own little corner but we're not really making music.”

This rings true. I’ve met lots of people playing catchy digital tunes in the NHS but without a conductor to tell them how everything fits together they risk creating a discordant mess.

Hi Jerry,

Very interesting. Quite a few big hospitals in the UK are now using Epic and like it. But not everybody is enthusiastic - I've heard complaints that it is hugely expensive and not very flexible when you want to extract data for research purposes.

"One patient one record" will never happen. Too many services are still relying on paper based records