Is the NHS App facing an Epic Battle?

Hospitals using American IT system finding it tough to share data

It was born in 2018 to a chorus of yawns but suddenly the NHS app appears central to the government’s drive to modernise the health service. Yet while ministers are trumpeting its contribution to cutting missed appointments, a giant American health IT supplier is providing hospitals with its own patients’ app rather than the one developed for the NHS.

Last week the Department of Health announced that since July 2024 a major reform of the app had stopped 1.5 million appointments being missed, helping to save over £600 million.

The Health Secretary Wes Streeting painted this as a victory for patient empowerment: “By putting the latest technology into the hands of patients so they can access services quicker, we’re freeing up more time for doctors and nurses to focus on treating people and getting waiting lists down.

When I went to see the then Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt unveil the app in 2018 he was similarly optimistic about what it could do as the health service celebrated a significant birthday. "In our 70th year as the NHS, we have to look forward as well as backward and the big change that is going to happen in the next decade is the technology revolution."

But that revolution was slow to arrive in a health service still using fax machines, and at first the app attracted little interest from patients. The pandemic changed all that, with the app’s function as a Covid passport encouraging millions to download it.

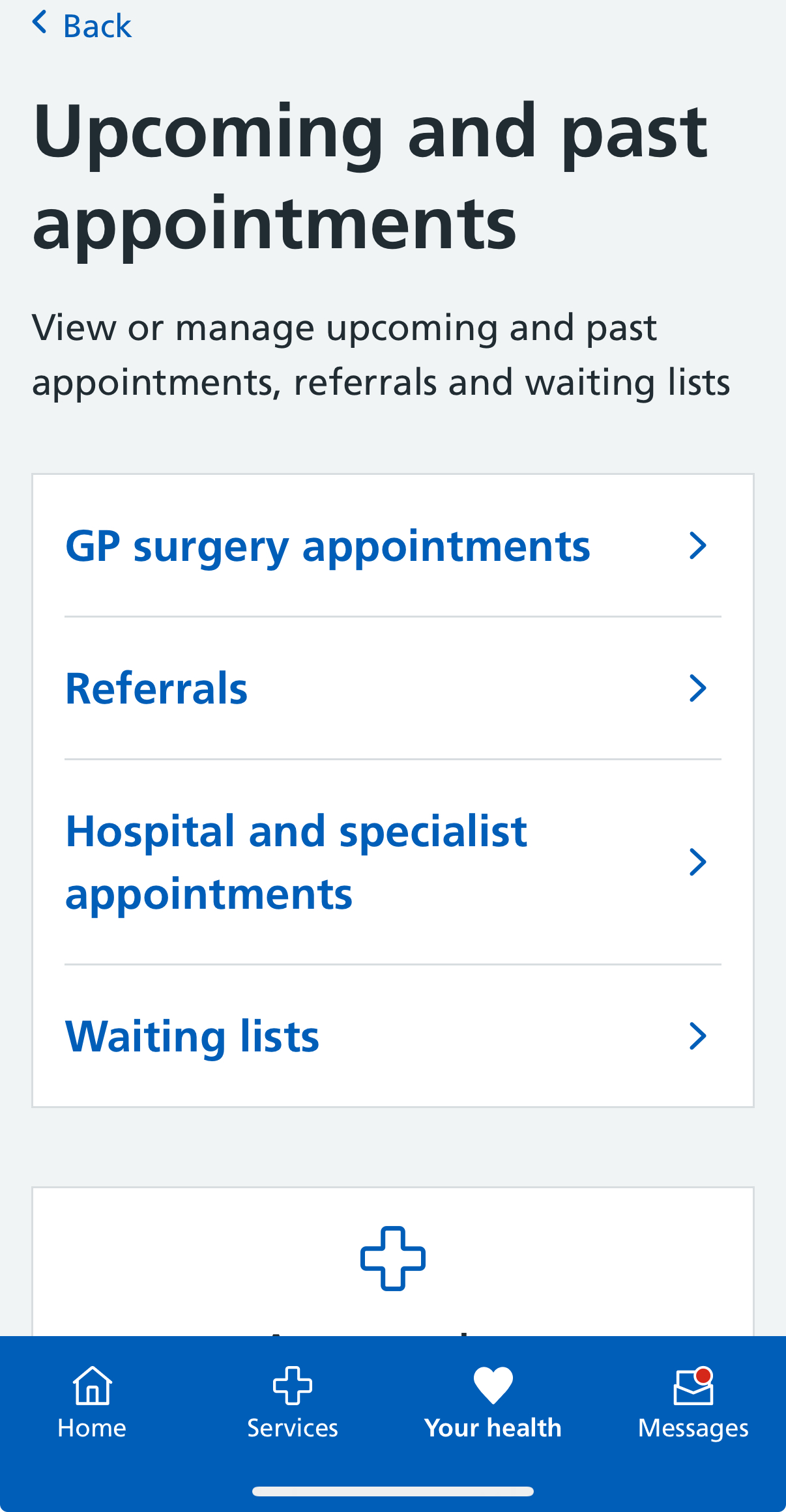

But to me the biggest attraction of the app as a patient who has dealings with a number of hospitals is as a one stop shop where you can keep track of forthcoming appointments, test results and correspondence between hospital doctors and GPs.

Here’s the problem, however. While the government is celebrating that 87% of hospitals have now signed up to provide data to the app, the remaining 13% include some heavyweight refuseniks. London’s Guy’s and St Thomas’ , King’s College Hospital and UCLH, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust and Cambridge University Hospitals also have something else in common - they are all customers of Epic, an American supplier of electronic patient record systems.

Now, Epic promotes its product as an all purpose IT system for hospitals with one of its key features a patient portal called MyChart, a slick app with 100 million users worldwide. It is this rather than the NHS App which its hospital customers use to inform patients about appointments.

I am a regular visitor to Moorfields Eye Hospital, which for twenty years has been treating me for an ocular melanoma, and to Charing Cross Hospital, where the neurologist and nurse overseeing my Parkinson’s treatment are based. It was a relief when after a bit of dithering both signed up to the NHS App and I could manage my appointments and my medication for both conditions on one platform.

But Moorfields also sends me to UCLH for regular MRI scans and because that hospital is an Epic customer news of an appointment arrived this week via an email taking me onto the MyChart platform. It was mildly irritating to have to go through the verification process before I could read the letter and find out about my appointment but the real annoyance comes later.

Reminding myself about my forthcoming Moorfields and Charing Cross appointments simply involves opening the NHS app but to look through the details of when and where I have to go for my scan means searching my immensely cluttered email inbox.

Why does this matter, I hear you ask. Well, any friction in a patient’s interaction with digital platforms is bound to have costs in terms of missed appointments - and that is a major problem for the health service.

Since first hearing about Epic I have been reading up about it and it seems in many ways to be an admirable business. The podcast Acquired, which specialises in examining the stories of tech companies with painstaking research, devotes four hours to its episode on the history of a software business that was a minnow twenty years ago.

Then, with a relentless focus on its hospital and health insurer customers, it began beating the likes of IBM to contracts to supply electronic patient record systems. And whereas big healthcare IT contracts have a history of going wrong at great expense, Epic’s customers seem to love it. Once signed up, they never leave - or at least the one which did desert Epic for another supplier soon returned.

The business has a very strong culture, driven by its 81 year old founder, the remarkable Judy Faulkner who has promised that the private company will never be sold, never go public and never acquire another business.

But another aspect of that culture is a deep aversion to collaborating with other companies, born out of a disastrous partnership twenty years ago with the Dutch electronics giant Phillips on a medical imaging project which cost both firms a lot of money. That means, say some critics, that Epic has an interoperability problem - in other words it tends to lock its customers into a suite of software that makes it difficult to operate with other products.

So is that why the company’s UK users can’t work with the NHS app? Or is Epic telling them that they just have to use MyChart instead? On Tuesday I contacted Epic, two of its customers, UCLH and Cambridge University Hospitals, and the Department of Health asking if they could shed any light on the matter. It really did not seem too tricky a question but by Wednesday afternoon I had heard nothing.

Then UCLH came back with an interesting response - no, Epic was not stopping the hospital from using the NHS app but it was a complex business:

“It has taken some time to find the correct technical solution to take appointment information from the Epic electronic health record software and display it in the NHS app. Acute trusts in England which use Epic recently agreed a solution with the software company and NHS England. Code development and testing will be completed towards the end of this financial year. Patients will then be able to see aspects of their hospital health record in the NHS app.”

I checked and “the end of this financial year” turns out to mean Spring 2026, so transferring my appointment details must be a fearsome challenge.

Then, after my bedtime on Wednesday, Epic sent me a pretty comprehensive response to my inquiry. No, a spokesperson said, it was not correct that Epic was standing in the way of hospitals using the NHS App:

“NHS England, Epic, and Trusts using Epic are working together to integrate the NHS App with Epic. With this integration in place, patients will have access to both the NHS App and MyChart—and the unique capabilities each offers.”

The statement hinted that Epic’s MyChart was far superior to the NHS App:

“As part of a unified EPR system, MyChart has full awareness of a patient’s treatment plan, care setting, and clinical context—enabling a highly personalised, real-time experience for patients and their families. Trusts using Epic have been clear that preserving these capabilities is essential to transforming care delivery and collaboration.”

But it would be made simple for users to switch between the two: “Patients will be able to jump from the NHS App to MyChart without needing to log in again--and vice versa.”

It is good to hear that Epic is not going to stand in the way of its customers using the NHS App. But what is striking is how complex and time-consuming an operation getting the two systems to talk to each other seems to be - certainly compared to what has happened with Trusts using other electronic patient record systems.

One of Wes Streeting’s goals in his bid to make the NHS more efficient is to see data shared more freely between hospitals that too often seem to regard that data as their property, to be guarded jealously. Perhaps he needs to have a word with Epic - that word being interoperability.

My husband is treated a Guy's which uses MyChart but his GP has no access to it because he is in a different trust. And the consultant at Guys has no access to the blood test results when they are done between appointments by the GP practice. All because apparently competition is good for patients.

Dealing with the digital infrastructure for my healthcare is frustrating and needs a significant amount of detective work. One hospital uses ‘Patient Knows Best’ another uses another system and they don’t all tie up with the NHS app. On the app I’ve had occasions where appointments have been booked I hadn’t been alerted to - and IT systems between trusts don’t ‘talk’ to each other. In some ways very helpful but a ‘work in progress’ definitely