Chapter 4 Raspberry Pi

Can Britain build a computer?

At first sight the story of the Raspberry Pi, the barebones computer designed to get kids coding, might seem out of place in a book about smartphones and social media. But it allows me to address some of the themes of this era - the anxiety over Britain’s failure to produce a tech business to rival the Silicon Valley giants, the concern that every child had a powerful computer in the form of a smartphone but no idea how they worked.

And there’s another reason to tell this story - for the device that went on to become the best-selling British computer ever made might never have got off the ground but for a smartphone and a social network. The smartphone was my iPhone and the social network was YouTube.

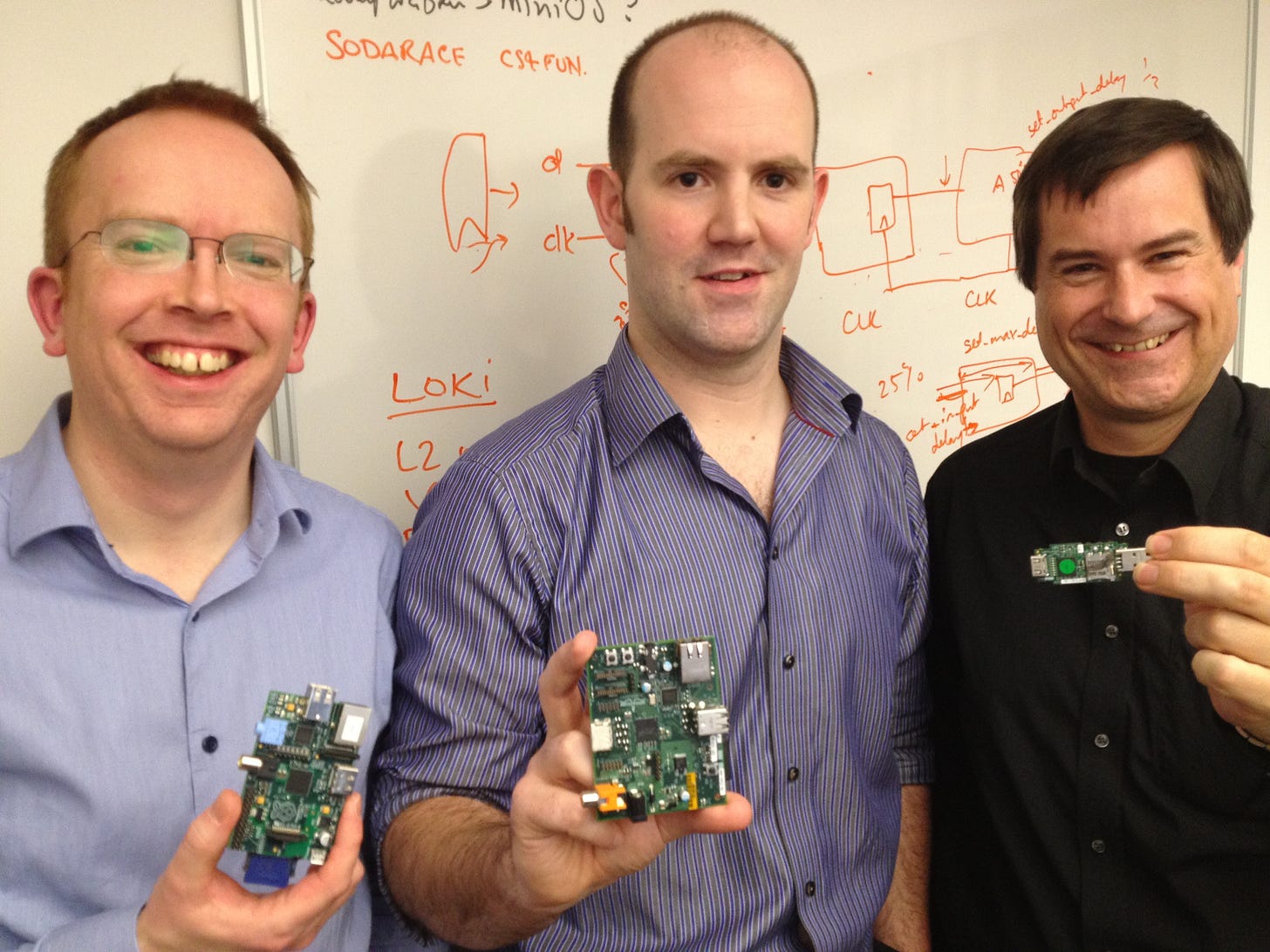

In May 2011 two visitors from Cambridge, games entrepreneur David Braben and computing academic turned chip engineer Eben Upton, came to see me in my office at BBC Television Centre in West London. They wanted to tell me about this ultra cheap computer they were designing with the hope of getting it to maybe 15,000 children who would be inspired to learn coding.

They were under the mistaken impression that I had some influence and could persuade the BBC to back it just as the Corporation had backed the BBC Micro, which in the 1980s ended up in just about every classroom. I had to put them right about what they said could be the BBC Nano - it wasn’t going to happen.

Nor could I call up a camera crew and get them straight on the news. But I was intrigued enough to whip out my iPhone and shoot a very simple one shot video with David Braben explaining the Raspberry Pi and its mission. You can see that video here - and this extract from the book explains what happened next:

I said goodbye to both of them, uploaded the video to my YouTube channel, and embedded it in a BBC blogpost about the Raspberry Pi project. Later that Thursday, I clicked on my YouTube page and was surprised to find the Raspberry Pi video had already had over 10,000 views.

I had started using the video-sharing service in 2006, just a year after it was founded, and uploaded a mixture of family and work stuff, from cheesy ski holiday videos to mobile phone launches. Most got seen a couple of hundred times, although my biggest hit at that point had been a review in 2007 by my nine-year-old son of a laptop aimed at children in the developing world, which had nearly 19,000 views. But the Pi video was going viral with a vengeance. Twenty-four hours later it had topped 130,000. My blogpost was getting comments, too, some applauding the ambition of the project, others sceptical, but after the Slashdot tech site linked to the video most of the traffic was going to YouTube rather than the BBC.

The viewer count continued to climb. By the end of the weekend more than 400,000 people had seen the video, and quite a few of them were getting in touch with the Raspberry Pi Foundation, wanting to know more, wanting to get involved. ‘I was getting one email a minute at least, if not an email every ten seconds,’ says Eben Upton. ‘I mean, it was a massive spike of emails.’

A couple of years later he was to describe this as the ‘Oh, shit’ moment: ‘We had to figure out how to make what we promised to do actually true.’ For David Braben, it made everything much clearer. ‘That discussion with you and the video was quite instrumental in us just saying, right: we’ll just go for it. And we’ll use our own name: Raspberry Pi, not the BBC Nano.’

Nine months later, on February 29th 2012, the Raspberry Pi went on sale, and this time I got the story on the Six O Clock News. Ever since that video went on YouTube, a feverishly excited community had gathered around the device and that day demand was so great that the sales websites were overwhelmed.

Around 100,000 Raspberry Pis were sold, leaving Upton and Braben and the rest of their small team with a bit of a problem. What I did not realise at the time was that at that stage only ten of the devices had arrived from China, one of which had been given to me to film, and only a total of 2,000 had been ordered.

To find out what happened next, and how the Raspberry Pi went on to overtake every other British computer, you will have to buy the book.

Luckily, it is on sale from May 13th.