Chapter 12: The App That Could Tame Covid

A political disaster but not a technical one

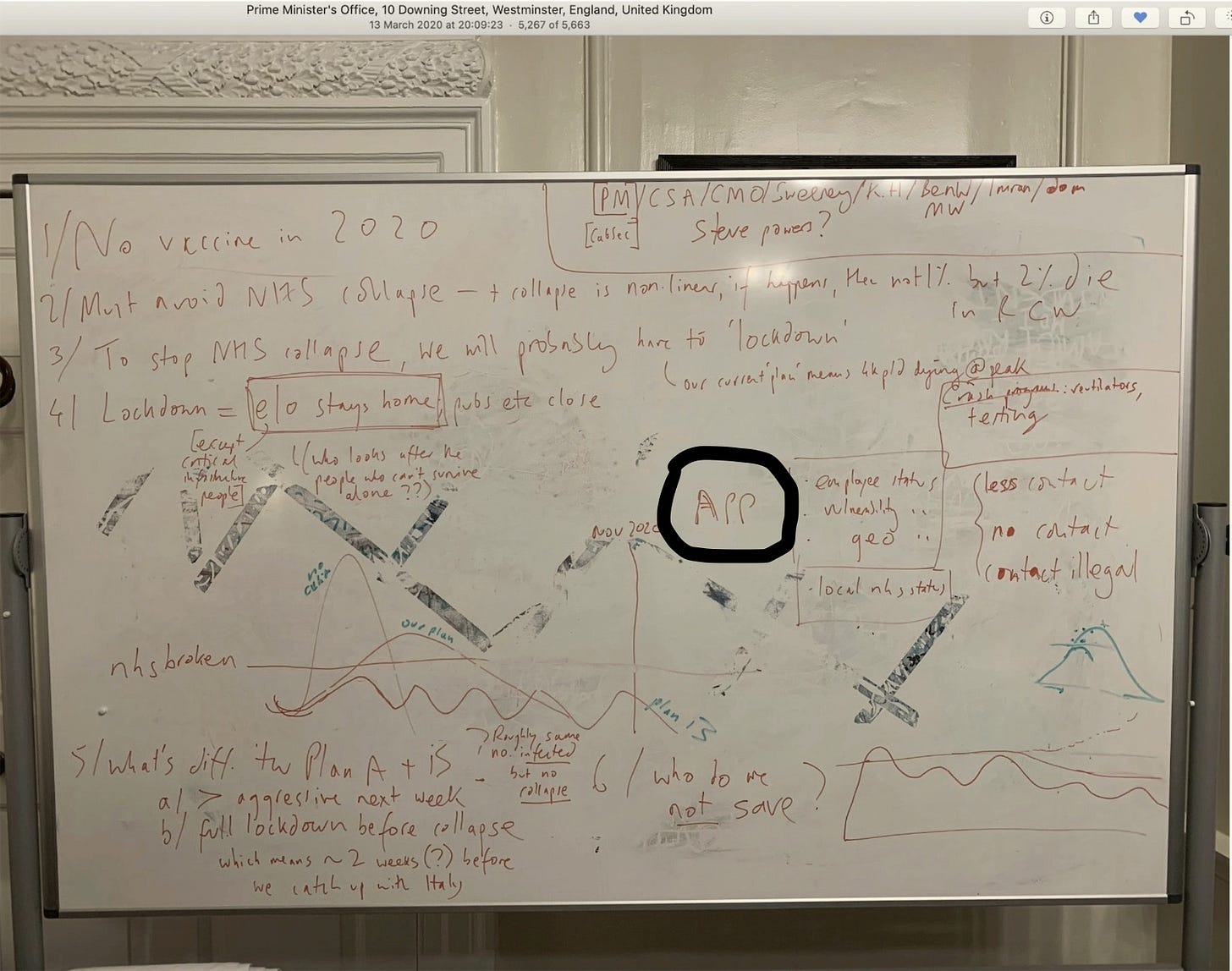

The photo above, presented to the Commons hearing where Dominic Cummings got a few things off his chest last week, was taken in 10 Downing Street on 13th March 2020. Right in the middle of the whiteboard sketching out the government’s coronavirus strategy at that time is the word “app” (circled by me), a clue to just how important a role a smartphone contact tracing app was supposed to have in the battle against virus.

In late March I got a message from an eminent figure in the technology world who wanted to tell me about “a very substantial project that will launch in days and potentially save hundreds of thousands of British lives.” This turned out to be the app and I was given privileged access to the team behind it.

This chapter tells the story of how, at least in its early version, the project to use smartphones to stop Covid-19 in its tracks went disastrously wrong. Faced with the nightmare of exponential growth in cases threatening to overwhelm the NHS, and without an effective manual track and trace operation in place, the government latched on to the idea of a technology solution.

But it quickly became apparent, as wiser heads from the tech industry had warned, that you could not build an effective Bluetooth contact tracing app “in days”. And as NHS managers, software companies, privacy campaigners and Downing Street tangled over the design of the app, the whole project began to creak at the seams.

What made things more complex was an announcement in April by Apple and Google that they were working on a privacy-focused decentralised platform for contact tracing apps. But the NHS team pressed on with their centralised app which they felt would give them a better overview of what was happening with the virus.

In late May, despite a trial on the Isle of Wight which appeared to show a healthy appetite to install the app, Downing Street was getting nervous about the project. This extract recounts what happened next:

By now, a government that had been given the benefit of the doubt by most people at the beginning of the pandemic ,and a Prime Minister whose own battle with the virus had won him sympathy, were under mounting pressure after a series of mis-steps, amid the growing realization that the UK was near the top of the league when it came to deaths from COVID-19. On 21 May, hoping to ease that pressure, Boris Johnson announced that England would have a ‘world-beating’ track-and-trace system from the beginning of June. It quickly became clear that this was a manual contact-tracing programme, and Downing Street briefed that the app was likely to come along a couple of weeks later. There was still a sense on the app team that just one more push was needed to get it over the line.

But the following day a story broke which was to dominate the news agenda for the next week, and undoubtedly made Downing Street even more keen not to launch something that might not work perfectly. The Guardian and the Daily Mirror revealed that in late March, when everybody had been told to stay at home, the Prime Minister’s chief adviser Dominic Cummings had travelled to Durham to stay in a cottage on his family’s farm while suffering from symptoms of the coronavirus. Over the next few days, first cabinet ministers, then the Prime Minister, and then Dominic Cummings himself, appeared in front of the cameras to defend what appeared to be a flagrant breach of the government’s guidelines. As more details emerged about the affair, notably Cummings’ half-hour drive to Barnard Castle to test his eyesight the day before the trip home to London, much of the public reacted with a mixture of laughter, derision and fury. An opinion poll carried out for the Reuters Institute in the last week of May found that less than half of people surveyed trusted the government to give them accurate information about the pandemic, down from two thirds in mid-April.

For a project that was all about persuading more than half the population to trust the government enough to put software on their phones which could in theory be used for mass surveillance, this was deeply concerning. ‘Barnard Castle was a head-in-hands moment – that was when trust was lost,’ a member of the app team told me months later. As May drew to a close, the Health Secretary was still promising a national roll-out in a ‘couple of weeks’, but by now the early enthusiasm on the Isle of Wight was fading, and people were getting restless for news. One of my contacts on the project told me the political environment was not helping – ‘The Cummings scandal will do untold damage.’

In early June version 2 of the app, featuring more symptoms and the ability to report tests, was ready for trials. From around the world, however, more evidence was coming in that showed that Bluetooth was not great at measuring distance – and that applied to all apps, centralized and decentralized. Don’t worry too much about this, I was told: these apps were public health tools, not scientific measuring instruments, and their accuracy should be measured against humans, who would be pretty poor at remembering how close they were to someone and for how long three days ago.

Now, this seemed a fair argument, if it weren’t for the fact that the NHSX team was going through the complex process of having the app registered as a medical device with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency – just one of the bureaucratic hurdles they now complained about having to clear. While the team kept promising that big things were about to happen – ‘Version 2 will roll out on the Isle of Wight on 8 June’ – I could hear growing frustration in their voices about the roadblocks being placed in their path by Downing Street, which they described as ‘extremely risk-averse’, demanding that the app be ‘bullet-proof’ before it was launched.

Meanwhile, other countries were moving ahead. France launched its centralised Stop-COVID app, which had drawn heavy criticism from privacy campaigners, and digital minister Cedric O said 600,000 downloads in the first few hours was ‘a good start’. Singapore, which by now seemed to have accepted that its app just was not up to the job, announced plans to give all citizens a wearable device in the hope that this would do a better job than a smartphone. On 14 June Germany became the biggest country to launch a decentralized app on the Apple/Google platform. It quickly outstripped France in terms of downloads, with something approaching 10 per cent of the population installing it within a few days.

But in the UK, ministers were repeatedly asked about the timetable for the NHSX app’s roll-out, and grew more and more shy and non-committal in their answers. The business minister Nadhim Zahawi said on a television programme the app would ‘be running as soon as we think it is robust’, and was eventually cajoled into saying that it would be out by the end of the month. Pressed at a Downing Street news conference, Matt Hancock would only say, ‘when the time is right’, and made it clear he wanted to focus on the manual tracing programme. Then on 17 June his junior Health Minister, Lord Bethell, gave the app a powerful kick into the long grass. ‘We are seeking to get something going for the winter, but it isn’t the priority for us at the moment,’ he told a select committee.

That evening we learned that Matthew Gould and Geraint Lewis, the two most senior figures from NHSX running the app project, would be returning to their main jobs, and that a new man would be taking over. Simon Thompson was an executive at the online retailer Ocado who some time previously had briefly worked for Apple. The message from the NHS PR team was that this was nothing to be excited about – the plan had always been for Gould and Lewis to mastermind the development of the app and then hand it over to someone else to oversee it in operation. But we smelled a rat.

The following day, just before lunchtime, my colleague Leo Kelion, who ran the BBC’s online technology news operation, rang me with an extraordinary development. A source had told him that the government was going to announce in a couple of hours that the centralized app was being ditched, and they would be switching to a decentralized model based on the Apple/Google toolkit. As there was only one source we could not go with the story yet, Leo emphasized, but we had to be ready.

But I had my own source. I texted them, ‘I’m told you’re going Apple/Google.’

Back came one word: ‘Yep’.

That meant we could break it straight away, so Leo wrote an online story and I tweeted this: ‘BBC scoop – NHS abandons centralized contact tracing app, moves to Apple/Google decentralized model.’

Within minutes I was breaking the story live on the BBC News Channel, and when I returned to my computer I found a Twitter Direct Message from what I think is known as a ‘very senior source’ wanting to brief me on background about the decision.

As the afternoon wore on, details emerged first in private, and then in public at the Downing Street press conference with Matt Hancock and Dido Harding, about what had gone wrong with the app project. That Isle of Wight trial that had been such a success? Actually it had been a bit of a disaster – Baroness Harding revealed that while the app had been good at detecting Android phones, it was no good at spotting Apple devices. In fact, it only detected 4 per cent of nearby iPhones. We also learned for the first time that a decentralized app, developed by the London branch of the Swiss firm Zuehlke, had also been trialled. It had proved much better at spotting iPhones, but surprisingly less effective than the original version at using Bluetooth to measure the distance between two phones.

At that Downing Street briefing Baroness Harding made clear her scepticism about the effectiveness of either type of app. ‘What we’ve done in really rigorously testing both our own COVID-19 app and the Google/Apple version is demonstrate that none of them are working sufficiently well enough to be actually reliable to determine whether any of us should self-isolate for two weeks, [and] that’s true across the world.’ Standing alongside her – or rather 2 metres apart – the Health Secretary struck a similar downbeat note about any kind of app being rolled out soon, while also suggesting that a lack of co-operation from Apple had stymied the project.

If Matt Hancock had hoped to deflect some of the blame it did not work. Apple was furious, and also insisted that it had not, as was claimed, been briefed about the switch to a decentralized app. And the next day the front pages of the newspapers were brutal – especially those which were normally sympathetic to the government. The failure of the app left the government’s contact-tracing strategy ‘in disarray’, said The Times. For the Daily Telegraph, which dubbed Matt Hancock ‘hapless and app-less’, the project was a ‘national embarrassment’. Worst of all, the conservative Daily Mail, the most powerful paper in Britain, asked ‘How Many More Corona Fiascos?’, detailing a string of U-turns on everything from testing to the availability of protective equipment, and laying most of the blame at Hancock’s door.

So the narrative was set, the app was a disaster. Social media knew what the story was - Serco had wasted £37 billion on useless technology. The truth was that Serco had nothing to do with the app, the true budget was in the tens of millions - a lot, but less than the Germans paid for theirs - and the tech team had achieved miracles, given the limitations Apple had imposed on what they could do with Bluetooth.

After I handed in the first draft of the manuscript in early September 2020. a working version of the app based on the Apple/Google protocol was released. It had a few wrinkles - people kept getting confusing alerts suggesting they had been exposed to the virus, which then disappeared when they opened the app.

But it did a reasonable job of altering people to contacts with the virus, such as standing next to someone on the bus, which a manual contact tracing operation would have been unable to identify.

The following May, a paper in Nature estimated that the app may have saved around 6,000 lives by telling people who had been in contact with the virus to self-isolate.But nobody paid much attention.

Back in March 2020, a naive belief in smartphone technology combined with a desperate realisation that a key part of any pandemic plan, a good old fashioned contact tracing system, was not in place made too many policymakers believe an app could be a silver bullet.

It wasn’t - but it did make a modest contribution to lessening the impact of the dreadful second wave of Covid-19 in early 2021. And for that the software engineers, who got on with their job while their political masters argued and dithered, deserve our thanks.

Always On is available as a hardback, ebook or audiobook here.

And if you want to support your local independent book shop you can order it at Hive.