Cell Replacement - Best Hope for a Cure?

Progress in quest to treat Parkinson's by transplanting dopamine cells

For those of us waiting for a cure for Parkinson’s, it has been hard to keep cheerful lately. The failure of the phase 3 trial of the diabetes drug exenatide and the long wait for the trial of the next big hope ambroxol have set back hopes of a breakthrough on the pharmaceutical front. But could another approach, cell replacement, offer more immediate hope for a cure? (And we will consider later just how we should define “cure”.)

Cell replacement involves finding ways of replacing the lost dopamine neurons in the brains of people with Parkinson’s, a mission which has been underway now for fifty years. Last week leading scientists in this field from Cambridge, Sweden, and Japan gathered in London, first to plan future collaborations, then to take part in a Cure Parkinson’s seminar where the general public could learn about recent exciting developments. I went along feeling rather sceptical - speakers at these events are often very hazy about how far they are from a genuine breakthrough - but emerged invigorated and hopeful.

Among those attending was Professor Anders Bjoerklund of Lund University in Sweden, the man widely regarded as the godfather of cell therapy. Way back in the mid 1970s at Lund University he started work on brain regeneration, pioneering ways of transplanting neurons into rats. By the late 1980s he was carrying out the first experiments using fetal cells and transplanting them into the brains of people with Parkinson’s.

Also present was the UK’s leading scientist in the field, Cambridge University’s Professor Roger Barker who has been collaborating with the Lund University team for nearly 40 years..

But the person who really brought the subject alive was Lund’s Dr Agnete Kirkeby who in a brilliant hour long presentation gave us the history of cell replacement from that first breakthrough by Anders Bjoerklund to a phase 3 clinical trial getting underway now. For a non-scientist like me it was a strenuous workout for the brain but Dr Kirkeby was the very best kind of teacher and I just about kept up.

She described the early work using cells from aborted fetuses - obviously controversial in the United States - to. treat drug addicts whose Parkinson’s had been brought on very rapidly after they injected synthetic heroin infected with a toxin called MPTP. A graft of dopamine neurons had a dramatic effect on some of the severely disabled trial participants, apparently unlocking them from their frozen state.

“This clearly showed us that this approach can work,” said Dr Kirkeby, ‘if you do it right, if you have the right cells, if you transplant enough cells, if the cells survive in the brain, they can, in cases like these, elicit a very prominent response in patients.”

But that is a lot of “ifs” and the technique proved hard to reproduce over the years that followed. Between 2015 and 2023 Professor Roger Barker led the Transeuro trial where 11 patients in Cambridge and Lund had cells implanted. Over the years, the scientists moved on from fetal cells, to stem cells gathered from embryos left over from an IVF cycle, and now to what are known as pluripotent stem cells which can be programmed to do just about anything, including becoming dopamine cells.

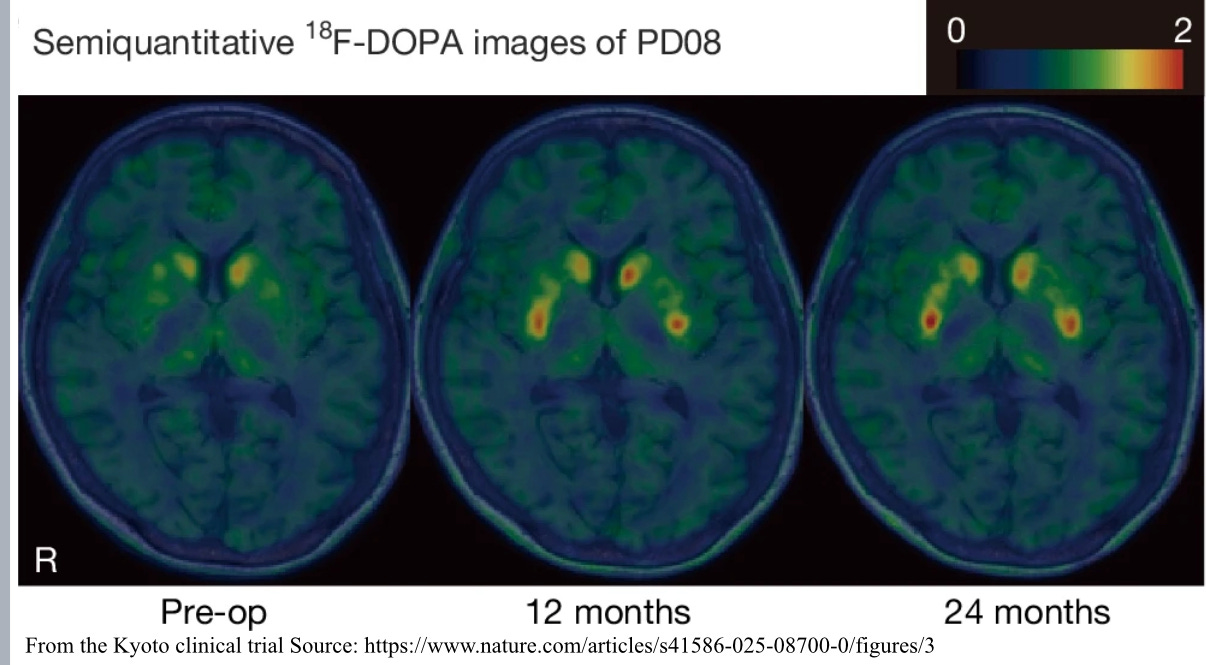

But results have continued to be mixed. Dr Kirkeby showed a slide with PET scans of a participant’s brain before the cell transplant, where there was very little dopamine activity and 18 months after when there was quite a lot. The same patient also got a much better score on the UPDRS scale neurologists use when assessing Parkinson’s symptoms. But others on the trial had not seen similar improvements in their condition.

These trials, it seems to me, do not fail in the way a drug trial does, where even if some participants do seem to get better you can put that down to the placebo effect which will soon wear off. But even if there are only a few examples, the cell replacement scientists can point to patients who, twenty years after the transplant, are still in much better health.

The challenge is to refine the technique and demonstrate through much larger trials that it can scale up and become an affordable option for clinical use. And here there was some good news.

New trials have been under way in the United States, Japan, China and South Korea and another Anglo-Swedish trial in Cambridge and Lund. At the seminar Roger Barker interviewed the final participant in that trial, Andy Cassy. He explained that the worse part was that at the beginning he had to take immuno-suppressive drugs to mitigate against the transplanted cells going rogue in his brain.

Andy was both very positive and realistic - he knows that it may be some years before his new dopamine cells begin to work properly but he has faith that it will happen. There are no results from this trial yet, but the BlueRock trial in the United States has released some data. There were two groups of participants, one given a lows does of the transplanted cells, the other a high dose.

The low dose group did not see a significant effect on their symptoms as measured by UPDRS, but those given a high dose saw a big decrease in their symptoms, with a 50% fall in their UPDRS score. But the really remarkable news is that Blue Rock has been given permission by American drug regulators to move straight from phase 1 to a phase 3 trial involving a large number of participants. This would be the final stage before getting approval to put cell replacement into widespread use.

The other great sign is that major pharmaceutical companies are now taking an interest in this technique- which is vital because the universities and charities which have funded most of the research to date would struggle to meet the huge cost of large scale trials.

But in the q&a session at the end of the seminar, I wanted an answer to the $64 billion question - when could this become available to the likes of me? Roger Barker surprised me with a very direct answer. He reckoned that the Blue Rock phase 3 trial could be completed by 2029 and if it was successful cell replacement would then be available as a therapy in the United States.

How quickly what would no doubt be a pretty expensive procedure would then be made available in the UK was far from clear but Professor Barker thought it coukd eventually be offered on a menu of possible treatments alongside Deep Brain Stimulation.

Someone else wanted to know whether cell replacement qualified. as a disease modifying treatment - something which slows, stops or reverses Parkinson’s. the “cure” in Cure Parkinson’s. Or was it just another symptom suppressing treatment like Levodopa or DBS?

While Roger Barker accepted that cell replacement did not attack the underlying causes of Parkinson’s, he indicated that anything that effectively removed your physical symptoms for decades might as well be a cure. And if it meant that there was a decreasing need to take dopamine replacement drugs with all their side effects, so mcuh the better.

Right now, with disease modifying drugs still looking to be at least five years away, it is heartening to see an alternative approach making progress. Hope is one of the most important medications for anyone with a degenerative disease and it has been in short supply, so thanks you to the scientists in Cambridge and Lund, in the United States and Japan, for giving us some reasons to be cheerful.

Professor Barker is my neurologist and I can’t speak highly enough of him. As well as being a leading light in PD research he is also a caring pragmatic person to lead you through those awful early days of diagnosis and onto a more hopeful positive view of how to deal with it day to day. He has made my journey so far a lot easier to navigate by being the consultant he is.

Glad you are saying what has become very clear from the progression of Movers and Shakers episodes.

Also ,- from the Women and PD episode -- if Oestrogen protects brsains who is findng out WHy and what use cn be made fothis

Also Michele HU thnks that Afiricans growing therir own Dopamine from Mucuna beanplants could help Paarkis therw ho cannot get the drgs we have. The retired head of medicne in Malawi and other Arican countreis lives near me Wolvercote, Oxfor.d she told me that Mucuna could not be ussd or approved even in africa without proper credible research. SO where is this research?