Can AI transform COPD care?

It seems unlikely but a spinout from a digital design agency could be about to transform the treatment of one of the most common and costly long-term conditions. The startup is Edinburgh-based Lenus Health and the condition is COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease), which affects 1.2 million people in the UK of middle age and older who in the main have been smokers.

The Business Development Director of Lenus Jim McNair explains that COPD is among a range of conditions - cardiovascular problems, back issues, dementia - affecting 20% of the population but accounting for 80% of healthcare spending. “There were over 110,000 admissions for COPD in 2022 - the large majority of those are preventable because the patient isn't being managed effectively.”

Jim hasn’t got a medical background, but he says Storm ID, the parent company from which Lenus was spun out, was all about user-based design, whether that was in the field of banking or health. He points out that healthcare is one of the few areas of modern life that has not been changed by smartphone technology and his company plans to change that.

The basic problem with COPD is that too many patients are being brought into hospital when they do not need to be and too many who do need urgent care are missing out and then arrive in emergency departments when they take a sudden turn for the worse. What is needed is a system that will be far more proactive, spotting problems in good time, and prioritising those who need care most.

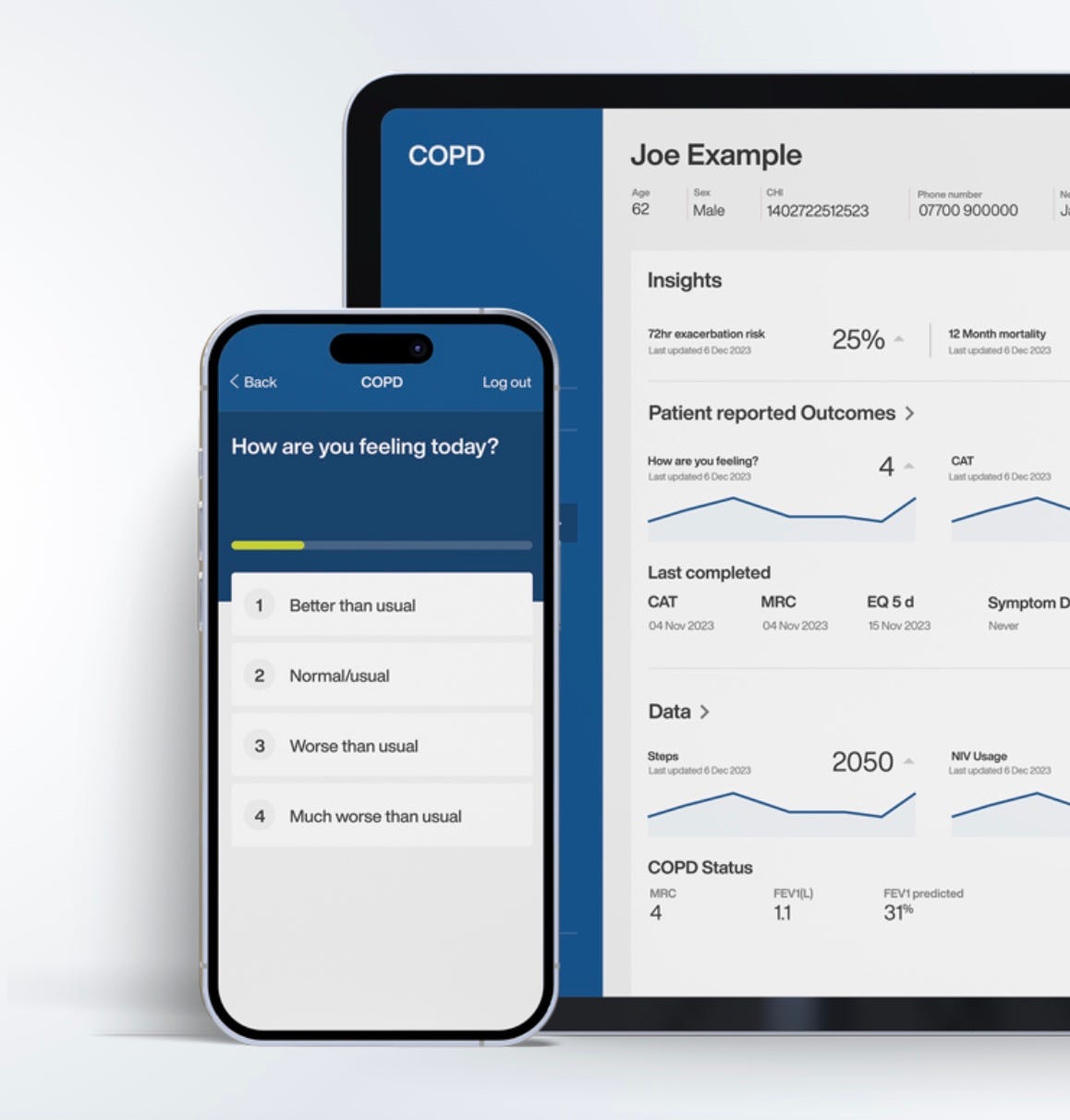

Jim explains that the answer is to collect a lot more data from patients using a smartphone app and then combine that with historic data about the way the disease progresses. For the first time, patients are being asked through the app to take an active interest in their condition:

“We're asking them standard question sets on a daily basis, which identify and help them understand their condition and those early indications of decline. So - what colour is your sputum? how are you feeling today? have you had your medication? - and getting them to think about how they're really doing.”

The next stage is for machine learning - which Jim McNair refers to as “statistics on steroids” - to begin to do its work.

“We're looking at what has happened historically in patient groups with diagnosed conditions - hundreds of thousands of different data points - and then applying those models to an individual to say, well if that happened the same way for 100 patients, it's very likely that that trajectory is going to happen again for that individual patient.”

He gives me an example from an ongoing clinical trial of the system which Lenus calls Stratify. One long term patient, who appeared to be doing well on his current medication, was nevertheless given a high risk score by the AI, meaning that he should be bumped up the list for an early hospital appointment. The doctors could not understand why until it emerged that the AI had unearthed the fact that ten years ago the patient had been diagnosed with cancer, albeit one which had been treated successfully. Such had been the turnover of staff that nobody remembered this - but the AI had read the notes.

I found this somewhat disturbing. Surely staff should know about a patient’s previous medical history without needing an AI to tell them? But Jim McNair pointed to the huge time pressures on doctors: “They typically have a 15 minute clinic appointment with that patient every six months, and they have a limited amount of time to assess and decide what the best course of action is.”

He is passionate in his belief that adoption of AI is the only way forward for an NHS buckling under intolerable pressure as supply of medical staff fails to keep up with rising demand from an ageing population. But, like many others I have interviewed for this series, he is wearily realistic about the time it takes from developing an AI product to getting it adopted for widespread use with patients.

Lenus has been lucky with government funding, from an initial Innovate UK grant to being selected for IDAP, the Innovative Devices Access Pathway Pilot Programme, which seeks to smooth the path of new technologies into the NHS. Nevertheless, it has taken five years for the idea which saw Lenus spun out of Storm ID to get to the stage where the results of that clinical study are soon to be published. Jim seems confident that Stratify has performed well and will get the regulatory approval it needs.

But it will then still need customers to sign up in what is a fragmented NHS: “There are 220 or so NHS Trusts in England, all of which are independent and are responsible for their own own balance sheet.” Jim points out that this fragmentation can be good for small businesses which have a better chance of winning contracts from local hospitals than if everything was decided centrally but it makes it harder for a company to achieve the scale it needs to compete globally.

Lenus Health has just those ambitions and is in the middle of a funding round to get the firepower it needs to scale up and take on overseas markets. “So we're hoping we're heading in the right direction, but it's hard yards, it's hard.”

Then he says with a grin: “But if it was easy, everyone would do it.”

Nadene, thanks so much. I'm enjoying meeting so many fascinating people trying to bring AI into the NHS

Something like the cancer should be at the top of a patient's notes. It astonishes me that doctors don't scan a patient's record for something like that.