Breast cancer scans - AI's biggest NHS success?

Kheiron Medical could be a home-grown worldbeater

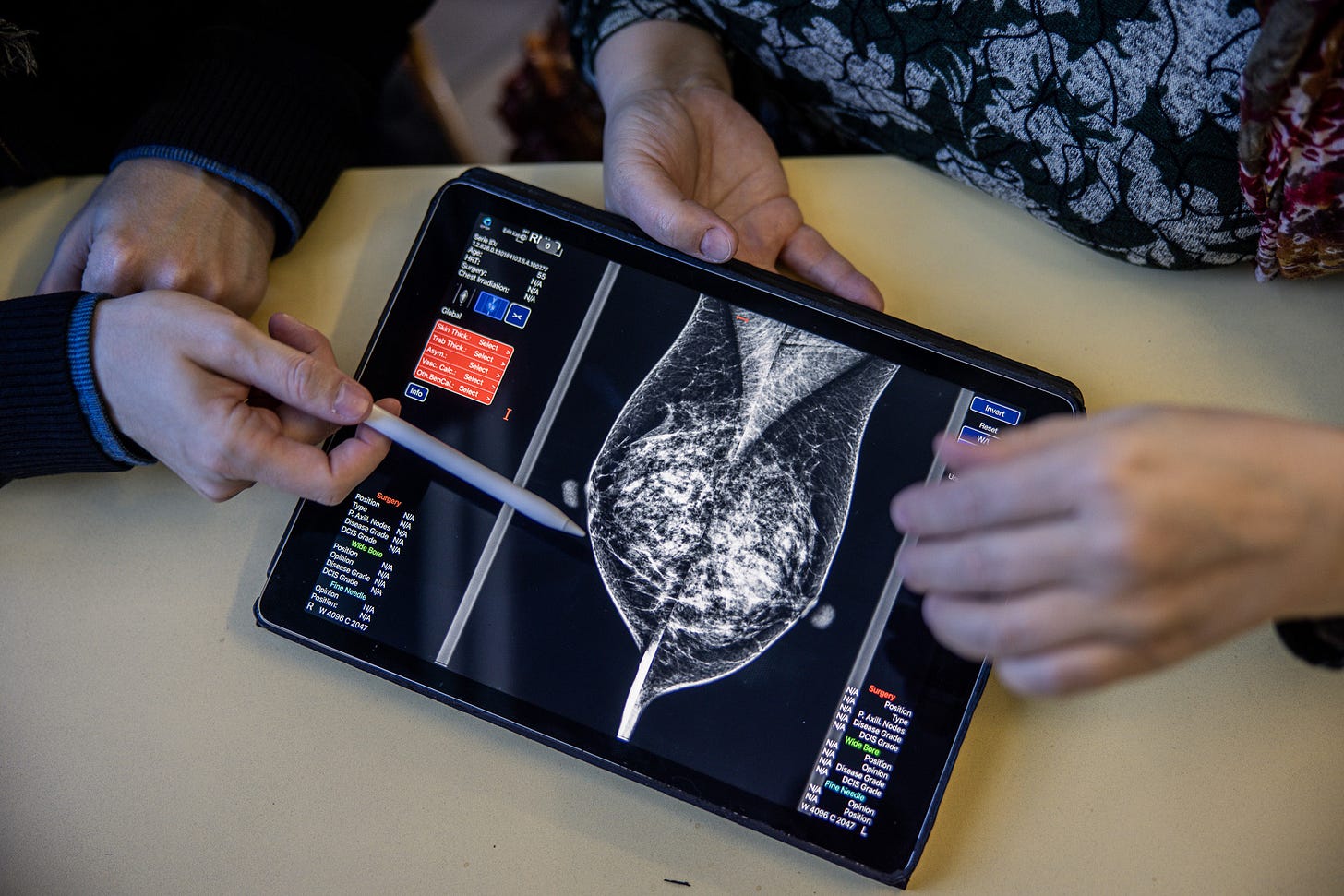

If there is one standout success so far for AI in the NHS it is Mia, the breast cancer scan tool built by Kheiron Medical. In March it won headlines for its ability to spot signs of cancer missed by doctors - read this excellent piece by my former BBC colleague Zoe Kleinman - and has been regularly cited by government ministers as evidence of the UK’s prowess in deploying AI in healthcare.

But when I spoke to Kheiron’s chief strategy officer Sarah Kerruish it became clear just what an extraordinary effort it had taken to get this far - and how the finishing line for deploying Mia widely in the NHS is in sight, but has not yet been crossed.

First of all, she says her company has experienced no lack of enthusiasm for AI in the health service: “The NHS is actually an amazing place to innovate. We've had tremendous support, incredible clinicians, lots of early adopters, lots of people really interested in going on this journey with us.”

But, just like Pearse Keane at Moorfields Eye Hospital, she is keen to stress that building a basic AI system to examine scans is relatively simple, turning that into something fit for clinical use - anything but.

“It's actually not that difficult to create a deep learning algorithm that works on a limited data set, but actually creating one that generalises, that works across different populations on hardware and different inputs, is extremely difficult and painstaking. And that essentially took us about five and a half years.”

She takes me through some of the stages. First, what’s called retrospective testing, trying out the algorithm on vast databases of past scans to see how it performs. Then Mia was tried on ‘unseen’ data - the kind it had not been exposed to before - in various parts of the country to see if it ‘generalised’, worked as well in Grimsby as in Greenock. “It's considered the holy grail of machine learning, to get it to generalise on unseen data and of course in healthcare it's particularly challenging because the data is so messy.”

That worked and then as they began to introduce Mia into clinical use on a number of sites in Scotland there were more phases of careful monitoring. In particular, they were on the lookout for a phenomenon called drift, where the performance gets less accurate because of some unforeseen external factor:

“It could be a new kind of software that's being used, for example, and the images look slightly different. It could be that the population is skewed slightly differently because of something like Covid.” She makes the point that drift also affects human radiologists and is something that needs very careful monitoring.

One broader concern, as piloting of Mia began on real patients, was whether it might lead to more false positives - women subjected to further unnecessary tests and all of the anxiety they entail when there was no cancer. But so far there has been no rise in the number of unnecessary recalls:

“We track the biopsies so we know. It's not just whether Mia thinks it's a cancer, or the doctors do or don't, we actually get the biopsy data. So we know definitively if Mia correctly called back a cancer or not.” What’s more, the data so far indicates that cancers are being spotted that were not identified previously by doctors. “We're expecting there to be an increase in the detection of really clinically meaningful cancer.”

So we come to the thorny issue if jobs. At the moment every breast scan is reviewed separately by two radiologists - surely if Mia is smarter than them you would be able to get rid of at least half of them? Well right now the final decision is still taken by two doctors but with reference to the advice given by Mia. So is that going to save the NHS any money?

Sarah Kerruish points out that Mia does only one part of a radiologist’s job but does it very well. “Radiologists will spend half a day routinely in a dark room reviewing thousands of mammograms looking for that needle in the haystack cancer.” Meanwhile, “Mia for example in Scotland ran 80,000 cases in a weekend. So the level of productivity and turnaround that that can deliver is quite remarkable.”

She points out that there’s a huge shortage of radiologists, described as a “ticking time bomb” by the Royal College of Radiology. “And AI is the only way that they're going to be able to solve that problem at scale.”

Mia appears to promise both better outcomes for women and greater productivity for the NHS. But while it has been used extensively in pilots Kheiron, which has spent large sums over the years developing the AI tool, is still waiting on the green light for its official adoption, and the revenue that will at last bring:

"We are hopeful, “ says Sarah, “that the results from the evaluations, trials and deployments we have conducted at 16 NHS sites will be the final unlock for the widespread use of Mia in breast screening in the UK."

Sarah Kerruish returned home to Britain in 2014 with a mission after years working with tech giants in Silicon Valley:

“The reason I joined Kheiron is because my observation was that in health tech, there are a lot of smart people wanting to solve important problems, but they don't really understand how doctors work and what they need, or how to get new technology adopted in this very complicated environment.”

In the company’s founders, machine learning expert Tobias Rijken and Peter Kecskemethy, brought up by a single mother who was a radiologist, she found two smart people who did have the skills and background to solve a huge problem - earlier detection of breast cancer. If Mia is as effective as it seems there will be demand for it worldwide - so let’s hope that the NHS can show it can be a leader in adopting technology made in Britain.

The time it takes for things to be adopted by the NHS should never be underestimated. I developed a simple algorithm, published in 2012, that showed that those with diabetes found to have no diabetic eye disease on 2 successive screenings were at very low risk and could be safely seen after two years rather than at annual intervals. This was then replicated in 7 more datasets, checked by teams at Public Health England, signed off by the Minister in 2017. It is now being rolled out in England, started in 2023. Things move slowly. I was told that it had been rolled out in Norway before it was rolled out in UK.